I remember reading this one a while ago when I first acted as Scrum Master for an Agile team and finding it really useful. I thought I'd revisit it to see how it holds up.

Overall Impressions

I'm still impressed by the breadth and depth of coverage the book manages - while keeping your attention with frequent vivid stories depicting how teams trying to use Agile can trip up or experience problems. It manages to give a quick but thorough run-down of general Agile principles and then a whistle-stop tour through the most commonly used Agile methodologies, comparing them and examining what the experience of teams using these techniques might look like, day to day. I think the book was a great grounding for me when I was new to the world of Agile, but I also appreciate the insights I can glean from it now after more experience. The anecdotes definitely ring true and are one of the best parts of the book - they remind me of a 'business novel' like The Goal, with characters who you end up rooting for to learn more of the Agile principles and succeed. I could see myself and colleagues at different times in the past in quite a few of them!

Cargo Cult Agile

A concept occurred to me while reading the book (I'm sure I'm not the first to think of it). It covers a lot of the sorts of situations explored in the book. Richard Feynman memorably described 'Cargo Cult Science' in a speech at Caltech:

" In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land."

In the same fashion, there are many examples of what I'd call 'Cargo Cult Agile' - companies that appear to have implemented Agile, that claim to practice it - but if you dig down below the surface and observe their actual practices (and results) you must conclude that they are not really practicing Agile. In the best cases, they have taken a lot of Agile ideas and good practices and are using them to help their business - but haven't committed to all parts of a technique or methodology ('Scrum-But'). At worst, they've just renamed their existing business processes to make them sound more Agile.

For instance, a lot of software businesses run a daily stand-up meeting for each team. Perhaps they do this because they've heard it's a good idea, or it might be that it's embarrassing not to, these days. But if you were to be a fly on the wall at that meeting you might find it's devolved into a daily status report to a boss, or that not everyone gets a chance to speak, or that it drags on for far longer than a stand-up should and everyone's sitting down because their legs get exhausted. Likewise, I'm sure that many people share the experience of being on a team that's pressed for time, on a tight deadline imposed from above, and begins to throw Agile practices by the wayside. If practicing Scrum, it feels as if there's not enough time to perform some of the Scrum ceremonies, so we won't do a Sprint Review this month, or we won't plan the next Sprint right away but just launch into doing things. But in reality every technique that's dropped leaves you less in control of your project's trajectory, stuck firefighting and unable to surface long enough to focus on what's really important.

The business stories in the book dig into this sort of situation and explore how and why it can come to be. The Scrum concept of 'Scrum-But' fits in well with a lot of the anecdotes in the book - ie when someone describes their Agile practice as 'Scrum, but we don't do xyz'. Sometimes everyone gets tired and lapses into a less effective way of doing things, but the most insidious is when a company have tried to adopt Agile, because they hear it's best practice, but don't really want to change the way they do things. So they neglect or ignore the parts of Agile that threaten the way they already operate.

The worst part of Cargo Cult Agile is that it leaves the impression on people - particularly graduates who don't have a wide experience - that this is what Agile means. They're often left with a lasting distaste for the labels of concepts that are supposed to help energise and jell a team. If your regular 'stand-up' meeting lasted 45 minutes and you often didn't get the chance to speak because it was dominated by senior engineers discussing issues with each other in depth as you leant against the wall and tried to stifle your yawns ... you're not going to be keen on going to stand-up meetings in future. And if you become a senior engineer, perhaps you'll feel it's OK to dominate Stand Ups with your longwinded technical discussions, since that's how you learned about the idea of a stand-up. This is not good for our discipline's professionalism.

There are valiant attempts to fight these tendencies by Agile practicioners worldwide. Training offered by the Scrum Alliance attempts to put the practice of Scrum in particular on a more professional footing, and it's a good sign when a company sends its employees on Certified Scrum Master training as a matter of course - it means they are more likely to have some form of committment to Agile. But there can still be a large disconnect - a chasm - between the ideals that someone learns on a training course, and the reality they experience when they return to the office.

Another avenue through which Agile can get more successful adoption is hiring Agile coaches to work alongside teams for weeks or months and coach them in the practices and techniques of Agile in person. These folks have a daunting job indeed. Not only do they have to convince the cynical programmers that they're working alongside that this management fad (for they will have lived through many) will actually make a positive difference to their work lives - they also have to convince top management that it is worthwhile. Often, organisations will have lived through multiple unsuccessful attempts at transforming software delivery into an Agile process. The pinnacle of success in Agile adoption is always fragile. It only takes a little more institutional inertia, a little more doubt from management to reverse such a transformation entirely.

Fundamentally at odds

It's easy to pick up a simplistic idea of Agile, but hard to put the principles into practice, because they involve things that management in particular is uncomfortable with - giving up control to the development team, not knowing in advance all the details of what will be made, trusting the people who will do the work to estimate the time it will take. As Thomas Lindquist points out, fundamentally what's going on here is a collision between the egalitarian values of Agile with the typical command-and-control corporate structure.

"The hard truth is that Agile and Traditional Management still don’t get along. In repeated polls of people working in many different firms where Agile and Scrum are being implemented, somewhere between 70 to 90% report tension between the way Agile/Scrum teams are run in their organization and the way the rest of the organization is managed. Generally less than 10% reported 'no tension.'" Steve Denning, Is Agile Just Another Management Fad?

This is a bit of a depressing realisation, because it means these problems are baked into many organisations from the start. Those who wish to implement Agile can naturally expect resistance, a constant struggle to preserve the ideals of the methodologies against the tendencies of their own organisation, unless they are lucky enough to work for a smaller organisation or one with a more egalitarian structure (or for themselves, of course).

As Jurgen Appelo observes in the foreword to Michael Sahota's 'Agile Survival Guide' (which I highly recommend for thinking about this problem),

"People don’t struggle so much with the adoption of Agile practices. They struggle with the transformation to the Agile mindset, because many organizational cultures actively resist it."

Why do they actively resist it? Sahota compares it to T-Cells in the immune system, designed to kill foreign elements in the body (organisation). When one team makes a successful transformation to Agile ways of working, they experience a reaction from other parts of the organisation - unless they can disguise themselves as appearing to do 'business as usual'. In one of his suggestions, this takes the form of a useless Microsoft Project Plan that has no value to them or their customers but is required by the organisation for their team to work without further disturbance. Sahota suggests that Scrum is actually too powerful a tool - he points out "Scrum is designed to disrupt existing power and control structures by creating new roles (Product Owner, Scrum Master, the Team). It also posits self-organizing teams as the fundamental building block of organizations. As such, it should be avoided if at all possible" as it will inevitably cause conflict and a complete failure of Agile adoption.

What is it that makes organisations so resistant to the very techniques that would help their workers do better work, become more closely connected to customers, have more control over their working environments and thus, be happier at work? Isn't that ostensibly what corporations want for their employees? Well, not really. Outside of vapid public relations exercises, what corporations actually want is what their shareholders want: to extract a maximum of profit from the efforts of their labour force, who they regard as interchangeable Human Resources. This leads to the dark side of Agile:

"[T]he danger [is] that people outside the development team will hear these metaphors and misunderstand them — as a promise of work at a greater intensity and nothing more. Thinking that, apart from that, Agile is business as usual. Still yearning to make more money out of predictability, lower skills and lower wages. Not understanding that the point of Agile is to be Antifragile."

Is your development team stuck in this sort of situation? How did you try to mitigate it? As always, I'm interested to know your thoughts via email.

Hello! First of all, I'm not dead (for all three loyal followers of this blog!) I got a fantastic new job at Cambridge Medical Robotics as a full-time Python developer, and have consequently had rather less free time for code musings lately. It's been about five months since I first joined and I'm finally starting to emerge from the new-job haze and find my bearings again. In fact, I had time to break my laptop - and fix it again - which is what I wanted to talk about today.

What happened?

I finally found the free time to update my laptop from Ubuntu 12.04 to the latest version of Ubuntu LTS (16.04) a weekend or so ago. I had been seeing the suggestion to update coming up for a while (... nearly a year, it turns out!) and ignoring it. But because I couldn't make a new game run with my old version of Ubuntu without installing a bunch of updates anyway, I finally decided to bite the bullet and do the full upgrade. I'd heard mixed things about how well the transition between versions went for other people, and I was also concerned about keeping my windowing appearance the way I like it, so I knew this would take a while and probably not be straightforward. I backed up my data and even made a list of the useful programs I currently have installed, in case things completely went sideways. What I was hoping not to encounter was ...

Anyone who uses an open-source OS will be familiar with this situation. There you are, sitting in front of what was once a beautifully working machine, questioning all your choices and trying to find out how to fix whatever the problem is. The spinal reflex of Linux is the command line. It's what's left when things go wrong. As Neil Stephenson's excellent In The Beginning Was The Command Line reminds us (although here he is actually talking about Windows vs Macs):

"when a Windows machine got into trouble, the old command-line interface would fall down over the GUI like an asbestos fire-curtain sealing off the proscenium of a burning opera. When a Macintosh got into trouble, it would present you with a cartoon of a bomb, which was funny the first time you saw it."

Why even choose Linux?

My motivations

When I got my first laptop as I was about to go to University, I decided to try dual-booting with Ubuntu (it was a Windows machine originally). Mainly it was an experiment - I'd heard that there were some cool coding tools available for Linux systems and I wanted to see what it was like on the other side. I was also kind of a cocky teenager and liked the idea of using a niche, obscure system, customising my laptop in some way. And, most importantly, I had a lot of free time - I took a year out before going to Uni, so aside from working in a gift shop (which didn't occupy my mind that much) I was able to spend time fixing up my laptop the way I wanted. After the inevitable teething problems, I got an installation I was happy with, and enjoyed it so much I ended up just using Ubuntu as my primary system and abandoning the idea of doing dual boot. I kept my system Ubuntu all through college, and though I was sometime concerned I wouldn't be able to complete assignments with it, I was pleasantly surprised by tools such as OpenOffice, which allowed pretty seamless integration with Word, Powerpoint etc. I also had a leg-up on some of my classmates, as when I got to Uni it turned out that the machines in our department all ran Linux installations, too. So I never really had a problem there.

Common fears

But what if there are bugs and I don't know how to fix them? I'm not some l33t hacker!

Returning to In The Beginning Was The Command Line, which really is a stupendous essay, we find a wisdom about bugs which definitely still holds out. Whatever OS you are running will not be perfect. There will be problems from time to time, and you will try to learn how to fix those problems. Neal Stephenson compares the OS situation to a crossroads with different competing auto-dealerships. Customers come there and 90% go straight to the station-wagon dealership (Windows).

The group giving away the free tanks only survives because it is staffed by volunteers, who are lined up at the edge of the street with bullhorns, trying to draw customers' attention to this incredible situation. A typical conversation goes something like this:

Hacker with bullhorn: "Save your money! Accept one of our free tanks! It is invulnerable, and can drive across rocks and swamps at ninety miles an hour while getting a hundred miles to the gallon!"

Prospective station wagon buyer: "I know what you say is true... but ... er... I don't know how to maintain a tank!"

Bullhorn: "You don't know how to maintain a station wagon either!"

Buyer: "But this dealership has mechanics on staff. If something goes wrong with my station wagon, I can take a day off work, bring it here, and pay them to work in it while I sit in the waiting room for hours, listening to elevator music."

Bullhorn: "But if you accept one of our free tanks we will send volunteers to your house to fix it for free while you sleep!"

Buyer: "Stay away from my house, you freak!"'

With an open-source OS like any of the Linux flavours, hundreds of people will be able to help you, and a solution will probably already exist online. StackOverflow and other such repositories of knowledge are great, as are reading the manuals and docs for specific tools you want to use. Whereas proprietary OS vendors are naturally interested in

a) Convincing consumers that there are no problems with their product (particularly security problems!)

b) Convincing shareholders that their product is commercial (not 'giving anything away for free') and worth paying money for

I don't think I can keep up with the skills you need to run an OS like that

Not going to lie, this can be a barrier. If you're like me and don't enjoy change, the process of continually needing to update and patch your open-source OS can be scary. You ask yourself - what if it doesn't work next time? You think about how you already voided the warranty on your machine by installing this crazy free OS and you question whether you'll be able to fix it.

To this I have several suggestions:

- Use an OS which has widespread adoption and is known to be easier to maintain, such as Ubuntu. I began with Ubuntu and continue to stick with it despite some gripes, because the canonical system does make it so easy to install the patches and updates you need to keep rollin'. Plus, the version system means you can go several years without needing to do a major upgrade.

-

Cultivate technically minded friends who can advise if things go very wrong. This can be online or off - Ubuntu has a warm community of volunteers who staff the forums and are generally very helpful and kind to newbies. If you're a student there is often at least one l33t sysadmin in your department who Knows The Ways of Linux and they are generally happy to help - perhaps in trade for chocolate! Depending on where you work your colleagues may be able to help out, too. Linux users tend to be evangelists who want to assist others to enjoy using the systems they do.

-

Comfort yourself by thinking of the various high profile problems with commercial OSes - at least you are not suffering with that!

-

Believe in yourself and your ability to fix things if they go wrong. I can't state this enough! Running my own installation of Ubuntu really helped in giving me the confidence I needed to get into coding and eventually, to get a full-time programming job. You don't have to be an IT professional to run Linux though - people from many walks of life do it for different reasons. One of my friends is a historian who uses Ubuntu to make cross-referenced notes more easily!

-

You don't have to commit to running an open-source OS full-time to give it a whirl and see if it's for you. These days you can fairly easily try booting Ubuntu or Debian from a memory stick. Using a Rasperry Pi will also give you a taste of Linux for a fairly small investment if you already have a separate screen and keyboard. And of course, dual-booting is getting easier to do - meaning you still have a full working installation of Windows alongside your Linux OS should you need or want.

Why continue with it?

For me in particular, it's important to know I have the ultimate control over my machine. As a programmer this is particularly important, since it is the tool of my trade - it's where I go to think and play. But I think the importance of control is true for everyone, if you think about what you use a laptop for. These days your computer contains your life - your bank statements, your music, photos, books, your email history, everything you've touched online. With a commercial OS, you have to admit that you are not the person who ultimately gets to decide what uses your machine can be put to. Whereas with an open-source OS, you call the shots.

Some concrete examples are in order.

I know that I will always fully own my digital books and music. I'm also confident I can make my own content through remixing the work of others, without being prevented from exercising my creativity.

I am a strong believer in the harmfulness of Digital Rights Management. Ultimately in order to enforce this notion (that these things do not 'belong' to you) someone else has to control your means to access them. Lawrence Lessig is far more eloquent than I can be about why it is harmful to lock off access to these things, so I would direct those interested in finding out more to his work which is, naturally, freely available online. I agree with him that the division between 'creator' and 'consumer' is artificial, and ultimately, harmful. I want to pay creators a fair prices for ebooks and music I enjoy, and in return to be freely able to use those purchases whatever way I see fit, just as I would a physical book or a vinyl record - to lend it to a friend, reshape or remix it. One of my hobbies is vidding. This is considered copyright violation of the video and music sources I use, and treated variously depending on my source material - sometimes fond indulgence, sometimes takedown notices and harsh threats. I am confident my OS will never prevent me from making my art, and that no-one else will get to decide what is acceptable for me to work on.

I can control my security and privacy and can be fairly confident that no-one is using my machine against my wishes.

"I just received an e-mail from my daughter, who is very upset, saying, 'Mom, I have my laptop open in my room all the time, even when I'm changing."

This is a big one. People may have heard of the laptops in Philadelphia that spied on schoolchildren and took tens of thousands of pictures of students, teachers and their families at home. The pictures were shared among staff and some were used to discipline students. One student was called into the Principal's office and accused of drug abuse after being secretly photographed eating pill-shaped Mike and Ike candy in his bedroom by his open laptop, for instance.

"[T]here is absolutely no way that the District Tech people are going to monitor students at home.... If we were going to monitor student use at home, we would have stated so. Think about it—why would we do that? There is no purpose. We are not a police state.... There is no way that I would approve or advocate for the monitoring of students at home. I suggest you take a breath and relax." Principal DiMedio in an email to a concerned student intern, 2008

"Among all of the webcam photographs recovered in the investigation there are a number of photographs of males without shirts, and other content that the individuals appearing in the photographs might consider to be of a similarly personal nature." Report of Independent Investigation Regarding Remote Monitoring of Student Laptop Computers by the Lower Merion School District, 2010

During the case, some argued this was fine, because the children didn't really own their laptops - they were issued to them by the school and the families had signed a consent form about the use of "TheftTrack" software. But the same argument can be made for any piece of proprietary software. Do you really read all of those EULAs before you click 'agreed'? If you use the iTunes music store for instance, you'll remember being forced to download a U2 album you weren't interested in and being unable to delete it. You might also remember the irony of Amazon remotely deleting ebook copies of George Orwell's 1984 from people's Kindles. What does your 'ownership' of a piece of proprietary software really mean, when the true owners are the company who created and retain ultimate control over it? Those companies do not necessarily have our best interests at heart.

This is an even bigger issue for those living in repressive regimes which seek to prevent free access to knowledge - Tor and other open-source anonymisation tools and open-source OSs are incredibly valuable to journalists, union organisers, and those working for the cause of human rights and free speech around the globe. The point of open-source tools such as Tor is that anyone is able use them completely freely, even those who the creators rightly despise.

I know that I can completely understand the tools I use, if I take the time to do so. I can even contribute to making those tools better for everyone.

This is a big one as a software developer, but also as someone who enjoys creating works of art. It's liberating to know that, even though I don't understand a great deal of the software I use, I can learn to understand it, and if it goes wrong, I can learn to fix it. The source and config files for Linux are not locked away or hidden. They are just text files that are freely editable - I can eternally change, customise (and definitely break!) my machine if I want. I don't have to stick with the settings that someone else thought would be best for people like me - I can alter how my machine works freely so that it works the way I want. This is particularly great for accessbility features such as screen magnification, audio readers and the ability to navigate without a mouse. The Ubuntu community is definitely ahead of MacOS in accessibility, and Windows to an extent as well.

Warm fuzzies

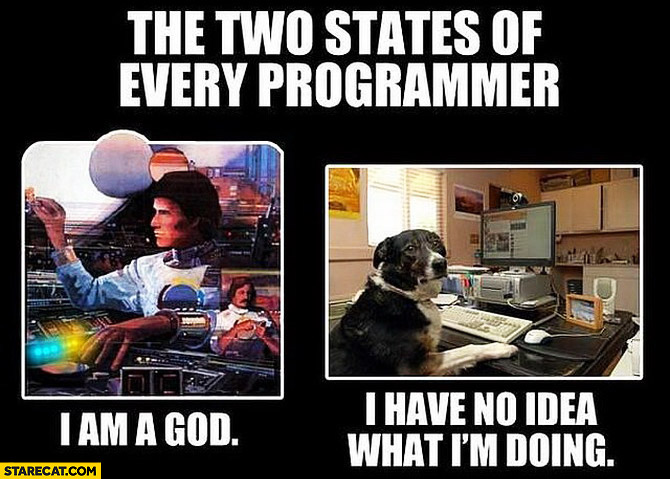

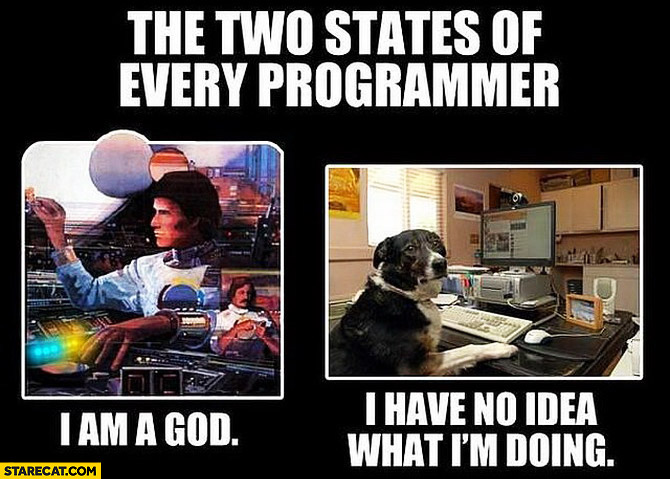

It's quite nebulous but I do enjoy the sensation of being part of a community committed to helping one another and to continual learning. It's also just fun to feel like I've taken the red pill and decided to understand more about how my machine really works! The thrill of having 'insider knowledge' and feeling a little bit like a hacker, that motivated my teenage self to go and install Linux, never entirely went away for me. Of course, there are sometimes feelings of being a fraud or not knowing enough. But the good outweighs the bad for me. As with other computer-related pursuits, I swing between two states:

And I wouldn't have it any other way.

And I wouldn't have it any other way.

So there you have it. Reasons why I continue to use a Linux OS, despite the sometimes-frustration.

Postscript: what was The Fix?

There's almost no point telling you about what fixed my particular problem, since googling for your specific problem will be far more effective. I've forgotten myself most of the details of what I did. However, if you're really curious, I do keep a notebook for these things (it's a nice way to learn a bit more for next time) so according to my notes, here is what I ended up doing:

- Pressed 'Shift' as my laptop booted up to access kernel selection and selected my previous happy kernel 3.13 to get into cmd prompt mode.

- Had a look around using the command line tools at my disposal - this was no hardship since on Ubuntu you can do everything with the command line - it just took me a little while to look up some of the commands.

sudo lshw -C Network showed me that network access was disabled - no good if I was going to try installing updates from the internet. sudo service network-manager restart did the trick and got that going again.

- At first I thought I had a problem with where I was pointing at repositories, so I checked that

/etc/apt/sources.list had the sources that a bit of googling led gave me a list of what to expect for 16.04. They were actually fine.

- I ran a

sudo apt-get upgrade and autoclean which seemed to fix some of the errors, but I still saw a message saying dpkg broken.

- Finally, I found out the fix on this handy bug report - looking in

etc/init.d/virtuoso-nepomuk showed me that my file there did indeed miss out a ### END INIT INFO at the end of its block. Using a command-line text editor (since I'm not a l33t Emacs or vim hacker, I just used nano) I fixed that and saved the file. After that, sudo-apt-get update worked. Following a restart, I had a GUI again!

- After that it was actually relatively simple to get the Gnome interface I know and love back (I really despise the Unity GUI, but that's another post).

That might sound overwhelming - and at the time there were moments of frustration for sure! It took me a few hours, spaced over several days. But I never doubted during this process that my OS problem could be fixed, and that I could be the one to fix it. It helped greatly that I have a tablet, so I was able to go on the internet during the crisis look up suggestions and solutions. These days, smartphones mean most people aren't trapped offline in a situation like this, and can find advice and help.

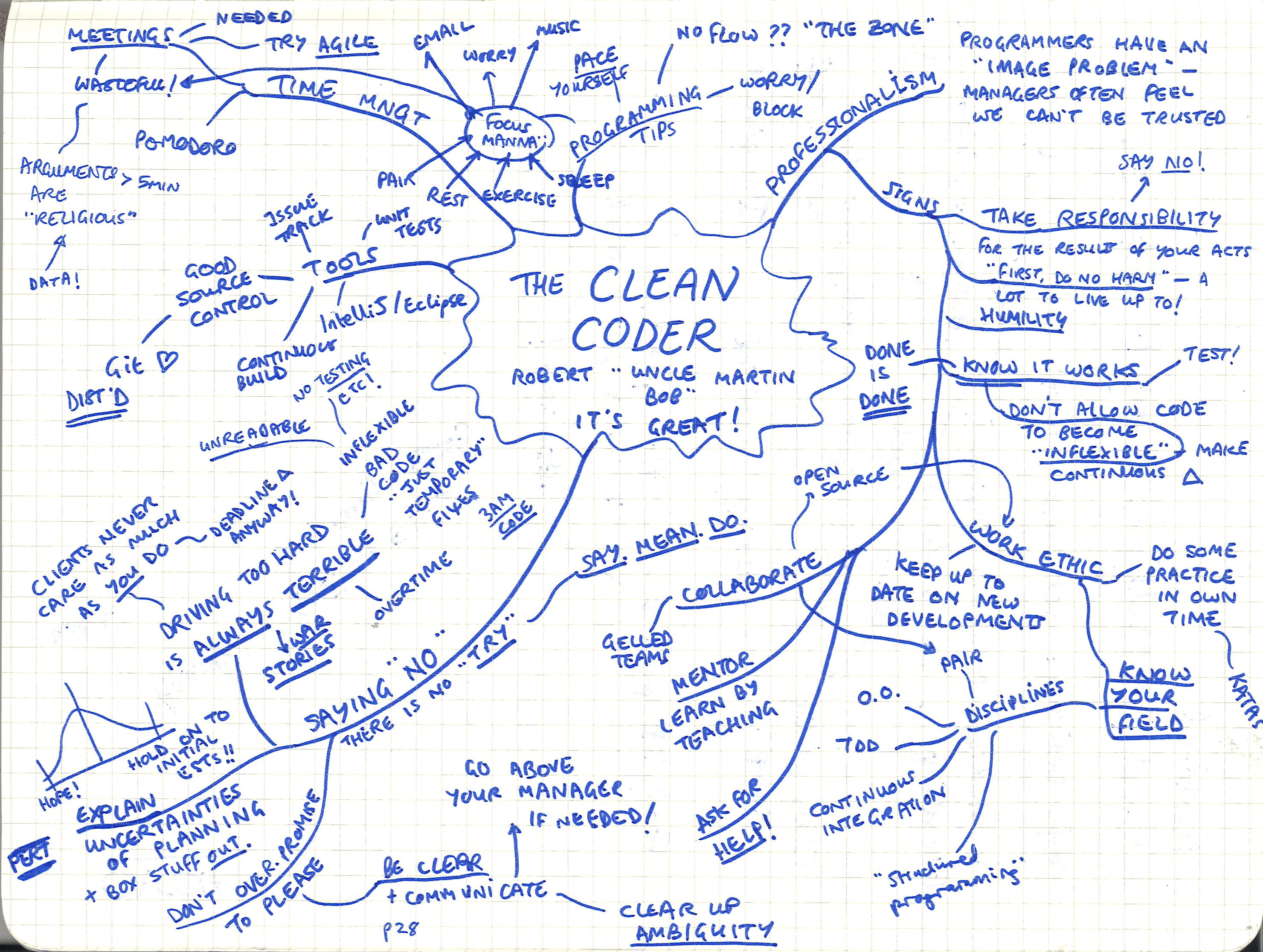

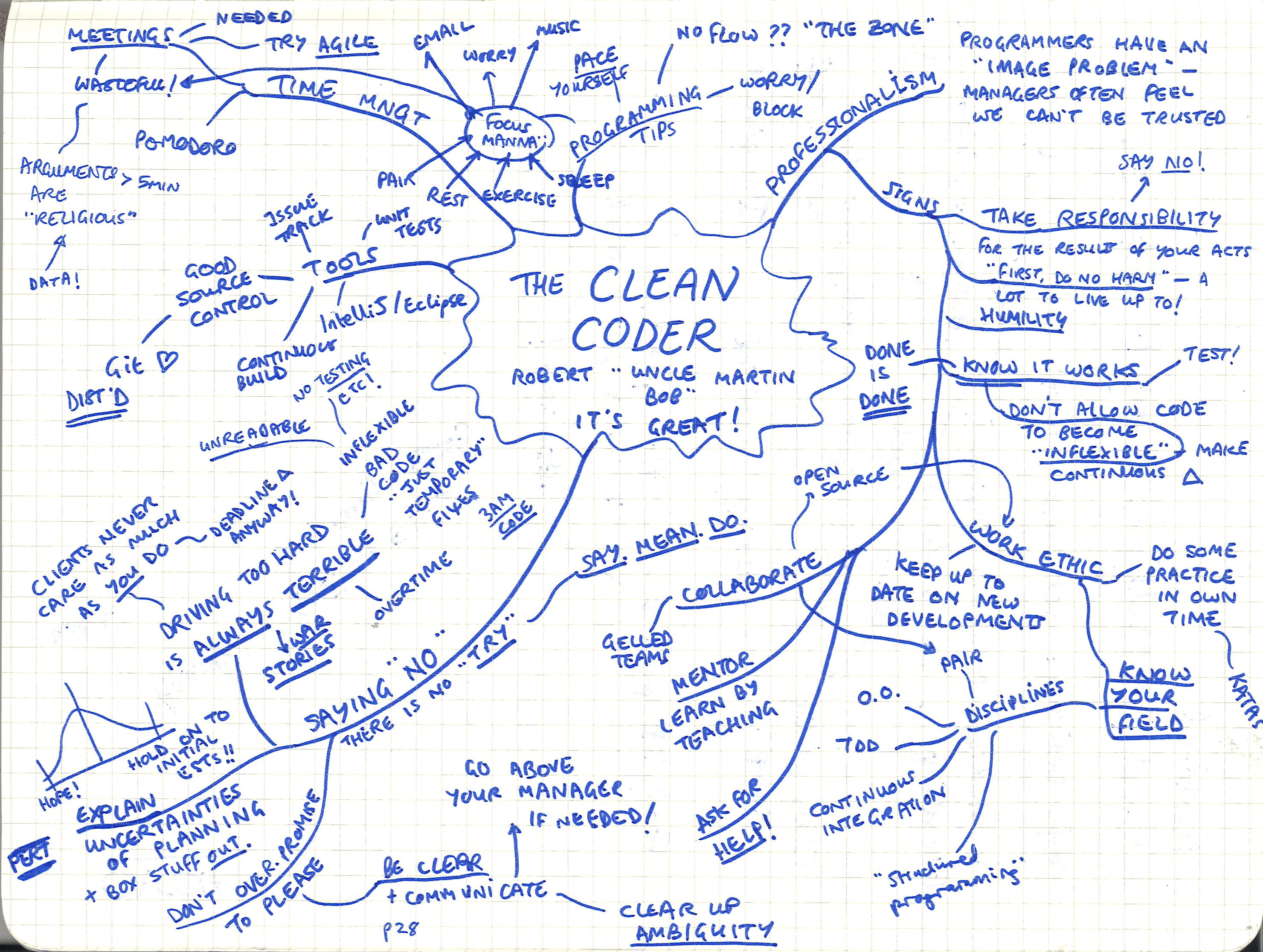

I was looking back through my mindmaps and came across this one, which I made when I first read "The Clean Coder" by 'Uncle' Bob Martin. I remember the book fondly and thought it might be fun to do a proper review.

Overall Impressions

The Clean Coder is a great read - Martin is a legend for a reason and his writing style is compelling, fun and readable. As the subtitle of my mindmap says, it's great! The book surprised me because it's not really about the mechanics of writing good code - it's all about professionalism (the 'clean' part) and having a set of ethics as someone who works in software. Martin uses some funny and horrifying war stories from his experiences as a novice programmer-for-hire to flesh out the book and explain what can happen when you don't have robust professionalism in your practice. I found myself nodding along as he described the team dynamics behind giving bad time estimates for completing a project, and how one of the most professional things you can do is sometimes to say "no" to tasks.

There is no "try".

There is no "try".

He also has some very insightful things to say about the dark side of 'Agile' practices, and how driving too hard toward a goal just-this-once is never a good idea. If nothing else, he points out, it doesn't even get you what you wanted! The code produced in those sort of conditions is invariably horribly flawed "3am code" and/or turns out to solve the wrong problem because those creating it were too busy trying to push something out the door to pay attention to the changing needs of their client. I'm reminded of this blog post from On Food and Coding:

With a given division of labour and a given level of skill, the proprietor can keep more money for themselves if they can get their staff to work for longer each day or to work with greater intensity. And when we deconstruct the terminology used by the most popular Agile process, Scrum, we find an unfortunate allusion to work at a greater intensity. For example, the week-by-week cycle of development is called an "iteration" in practically every other software process, including Extreme Programming. In Scrum this time period is called a Sprint. What associations does that conjure up? Well when you sprint you make an extreme effort to go as fast as possible, an effort that you can only keep up for a short time. That's what "sprint" means in everyday life.

Martin viscerally describes the sort of race-to-the-bottom conditions that this, coupled with optimistic overestimation of one's own ability to finish tasks, can induce.

Some reservations

One thing I disagree with is the amount of time he suggests allotting to your own personal practice - pairing with new people, doing Code Katas, listening to podcasts on software, picking up a new language, generally honing your craft. I absolutely think it's important to make sure you do some of this stuff outside of work - one of the reasons I started this blog is to motivate myself to learn more by providing a place to write about what I'm learning and have some accountability. But the time he suggests blocking out (20 hours!) is just unrealistic for most people. I think this very high bar is more likely to discourage would-be software folks from jumping into the field. I think understanding more about Martin's background explains where this comes from - he has a typically American 'Sleep is for the Weak!' attitude which has only partly been mollified by his realisation that if you work for too long, you stop producing things of worth because you're unable to concentrate well enough. Martin doesn't quite go far enough with his observations on 'Focus manna' to encompass leisure-time programming as well. Following his arguments, I have limited time in the week to practice my craft before I'm too tired for it to be of use - and I'm sure that line falls in different places for different people.

And I wouldn't have it any other way.

And I wouldn't have it any other way.

There is no "try".

There is no "try".