Flex and Bison

I recently started to learn about flex and Bison - a set of parser creation tools for C, C++ and Java. By specifying the grammar and rules for parsing inside two files, blah.y and blah.l, the flex and bison command-line Linux tools will auto-generate an appropriate parser in your chosen language. As you might imagine, this is very handy.

Since it's generally better to show rather than tell when it comes to software tools, here's a toy project I've been playing with in which I'm using them to parse GCODE.

The flex part is what's called a lexical analyser - it uses regular expressions to split the input into tokens. These tokens are used to generate a parser with the Bison part, which is the grammar that tells the parser what do do when certain tokens are read side by side.

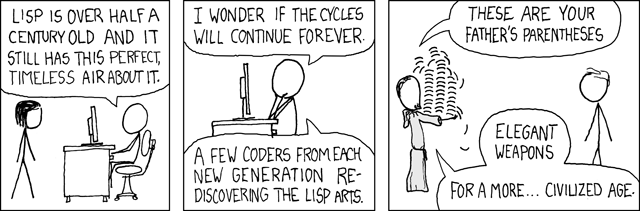

What particularly struck me about these tools was just how old they are.

Bison is a descendant of a tool called Yacc (Yet Another Compiler Compiler) which was developed by Steven Johnson working for Bell Labs back in the early 1970s, inspired by Donald Knuth's work on LR parsing. It has been rewritten in many different languages over the years, but the most popular implementation these days is probably Bison, which dates back to 1985, when it was worked on by Robert Corbett. Richard Stallman (yes, that Richard Stallman) made the GNU-Bison tool Yacc-compatible.

Flex meanwhile was written in C by Vern Paxson in 1987, tranlating an older tool called Lex. Lex was originally written by Mike Lesk and Eric Schmidt, and described in a paper by them in 1975. It was initially written in ratfor, an extended version of Fortran popular at the time.As they point out in the paper:

"As should be obvious from the above, the outside of Lex is patterned on Yacc and the inside on Aho’s string matching routines. Therefore, both S. C. Johnson and A. V. Aho are really originators of much of Lex, as well as debuggers of it. Many thanks are due to both. The code of the current version of Lex was designed, written, and debugged by Eric Schmidt"

As you might expect of such venerable tools, they have some excellent tutorials on their use, including an O'Reilly book "flex & bison" - which itself is the "long awaited sequel" to the O'Reilly classic, "lex & yacc". Those who teach in depth about these tools or about parsing are in some danger of re-writing them even more nicely in a favourite language - the linked example is PLY, which was originally developed in 2001 for use in an Introduction to Compilers course where students used it to build a compiler for a Pascal-like language.

I'm fascinated by how tools like this have survived and thrived over what, to computer science, is an enormous amount of time. Perhaps it is because they are beautiful - they have some inherent quality that shines out, no matter what language they happen to be in. I was re-reading the interview with Fran Allen in 'Coders At Work' about beautiful code, and it really resonated.

Allen: One of the things I remember really enjoying is reading the original program - and considering it very elegant. That captured me because it was quite a sophisticated program written by someone who had been in the field a while - Roy Nutt. It was beautifully written. Seibel: What makes a program beautiful? Allen: That it is a simple straightforward solution to a problem; that has some intrinsic structure and an obviousness about it that isn't obvious from the problem itself. I picked up probably a new habit from that of learning about programming and learning about a new language by taking an existing program and studying it. Seibel: How do you read code? Let's say you're going to learn a new language and you find a program to read - how do you attack it? Allen: Well, one example was one of my employees had built a parser. This was later on for the PTRAN project. And I wanted to understand his methods. It's actually probably the best parser in the world - now it's out in open source, and it's really an extraordinary parser that can do error correction in flight. I wanted to understand it, so I took it and I read it. And I knew that Phillipe Charles, the man who had written it, was a beautiful programmer. The way I would approach understanding a new language or a new implementation of some very complex problem would be to take a program from somebody that I knew was a great programmer, and read it.