Jan 30, 2026

You're beautiful but I can't work with you.

You're beautiful but I can't work with you.

One of my favourite books for thinking about the topic of interface design is the classic The Design of Everyday Things. I try to set aside time every few years for a re-read, and each time I get something new from it. It's assigned reading for Industrial Design students, and with good reason. It dissects why we might find it easy - or difficult - to interact with our environments and to use the everyday tools that surround us. It is wonderfully scathing in showing examples of dodgy design and makes the reader into a keener observer of the good and bad design choices all around them. You'll never look at a door handle in the same way again.

Disenchanted

I was given an Apple Magic Mouse to go with the Mac I was using at the time. It looks great, right? So sleek, like something from a science-fiction film. The only trouble was, I hated it. I tried to work with the Magic Mouse for a while, but I just didn't take to it. It didn't feel right in my hand and I never got used to the buttons. A bit embarrassed, I ended up returning to my boring, well-worn old mouse.

Back to old faithful.

Back to old faithful.

So why didn't the Magic Mouse work for me? I realised why as I read through the Design of Everyday Things. It explains,

"The human mind is exqusitely tailored to make sense of the world. Give it the slightest clue and off it goes, providing explanation, rationalization, understanding. Consider the objects, books, radios, kitchen appliances, office machines and light switches that make up our everyday lives. Well-designed objects are easy to interpret and understand. They contain visible clues to their operation. Poorly designed objects can be difficult and frustrating to use. They provide no clues. Or sometimes, false clues."

There are no visible buttons on the Magic Mouse and no wheel for scrolling. Like a door without an obvious handle, it relies on your previous experience of using a mouse to make sense of it. You have to map what you know about mouse buttons and scrolling onto its blank surface, in order to use it. I didn't enjoy this, and I also missed the tactile feedback that I used to get from scrolling the mousewheel. It turns out that's quite important to me, especially when working on graphic design or video editing. I'm not ashamed to have returned to my dull old device, with its comfortable size, obvious buttons and nineties-era scroll wheel. Those features are what helped me to use it easily.

Apple and Design

Apple has a long history of being concerned with good design. They are famous for their focus on usability. This talk at an Apple Developer conference by expert Mike Stern is a great example of the kind of solid thinking they usually do in these areas. I often return to it when thinking about user interface design and making apps more accessible.

So they understand the problem. But the company seems to have lost its way a little bit when it comes to hardware. You may recall the controversy when it decided to get rid of the headphone jack on the iPhone 7. I still carry around a headphone adapter so that I can use my favourite (non-Apple) headphones with my iPhone, and things may now have started to swing back in the other direction. And then of course there's the Magic Mouse. I'm not the first person to dislike it.

A common thread in these hardware choices is that they tend to be done for what seem to be aesthetic reasons. The desire to simplify the physical appearance of the hardware to make it look beautifully minimalistic has won out over functionality. Why is that?

To understand this drive to simplify helpful features away, it might be useful to learn a bit more about the history of architecture.

Minimalism

You'll have heard of minimalism. These days it's code for throwing out all your stuff so you can live more simply, but it became a powerful force in modern architecture and design in the early twentieth century.

By Hans Peter Schaefer - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52728

By Hans Peter Schaefer - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52728

Here is an influential example - Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's German Pavilion for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona. With stark planes of gleaming glass and marble, it exemplifies his design philosophy of 'less is more' and stands in sharp contrast to the lush ornamentation, colour and decoration in the structures of other architects. It looks relatively unremarkable to modern eyes but at the time it was a shocking departure from accepted norms.

Mies pioneered the principle of the 'free facade', now used widely in modern office buildings. Basically, the interior walls no longer needed to do the work of supporting the roof, the support function being transferred to unobtrusive supporting stilts. The walls appear to float or to be made of glass, and they disappeared to give huge open-plan interior spaces. It disconcerted visitors. People were unable to 'read' the building using their existing knowledge of architecture, because it deliberately hid its functionality. It felt as if the roof might fall down and crush them.

Another way

One of my favourite places in the world, La Sagrada Familia. My own photo, CC-BY SA 3.0 if you'd like to use it.

One of my favourite places in the world, La Sagrada Familia. My own photo, CC-BY SA 3.0 if you'd like to use it.

Another architect working around the same time was Antoni Gaudí. His creations also surprised conventional society, but for different reasons.

His designs did not hide support structures or place them in unexpected locations, but worked with the limitations of existing materials in ways that were visible and obvious. Large glass panes strong enough to support a wall or be used as a door were impossible at that time, so Gaudí used doors fragmented by organic shapes in metal resembling the structure of a leaf or spider web. Some saw his work as ugly, complaining that he had made buildings look grotesque, half-melted, like insects, and so on.

Gaudí did not separate interior and exterior with hard planes but intertwined them, deliberately echoing the structure of a forest and with some of the same advantages. His buildings still don't need much air conditioning even in a hot Barcelona summer because of the way they are designed to let air to flow through them, using decorative shutters to shade the rooms. He was ahead of his time in looking for these solutions inspired by nature.

I think you can tell which one I prefer. But Gaudí's way of building did not win. It's rare to find a modern office block without a free facade, and especially rare to work somewhere that isn't open plan.

No room for mistakes or adjustment

To build something designed by Mies and his modernist successors requires painstaking attention to detail.

Charles Jencks, in his 'The Problem of Mies' essay points out

"There is no place for a mistake in his absolute universe, because extreme simplicity makes one hypersensitive to each inch of a structure and the Platonic form, with its transcendental pretension, demands utter perfection."

Later adjustments are very difficult. The outward strength and modernity of these glass-fronted buildings is undermined by how delicate they can actually be.

By Simon Letouze - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NGC_006_ngc_front_facia_reduced.jpg

By Simon Letouze - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NGC_006_ngc_front_facia_reduced.jpg

People get angry when they realise that despite their looks, modern buildings can be more expensive to maintain than traditionally-constructed ones. The National Glass Centre in Sunderland is a tragic example. From the BBC:

"A spokesman for the University of Sunderland said it had commissioned a "full, up-to-date, independent building survey" in 2022, where external specialists concluded that a multimillion-pound investment would be required to address the longstanding problems with the building."

It is particularly painful that the seamless-looking design of the National Glass Centre, with its modern planes of steel and sheets of glass, is exactly what makes it so difficult to care for. It shone when it was new, but now it looks unlikely to outlive its architect. It will apparently be cheaper to tear it down and rebuild entirely than to fix it.

A Pattern Language

This brings us - rather neatly - back to programming.

The first book I would save from a house fire

The first book I would save from a house fire

This is my copy of 'A Pattern Language' by Chistopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein, Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King and Shlomo Angel. It's part of a series of books on planning and architecture written by their group in Berkeley in the 1970s. It lays out in very practical terms ways to design pleasing spaces. It has recipes for everything from the very large town planning level all the way down to what height you might place a windowsill to give a comfortable window seat. I love it dearly. I have used its suggestions in my daily life and enjoyed the results, and when as a teen I dreamed of becoming an architect the Berkeley group were the ones who I looked up to.

Their ideas have had unexpected resonance in the programming world.

When Object-Oriented programming was emerging as an interesting new way to design systems, Alexander was invited to speak at the OOPSLA (Object-Oriented Programs, Systems, Languages and Applications) conference in 1996.On the podium he looks slightly bewildered and comments,

"I'm addressing a room - a football field! - full of people, and I'm afraid I don't know hardly anything about what all of you do... My association with you, if you want to call it that, began about two or three years ago when a computer scientist called me and said there were a group of people here in Silicon Valley that would pay $3000 to have dinner with me. I thought, what the hell is this!"

He was greeted by programmers very enthusiastic to talk with him about 'design patterns' in software. Richard Gabriel, then working at IBM, was one of the first software engineers to draw links between the architecture of buildings and the design of code. His thoughtful book Patterns of Software: Tales from the Software Community was later published with a foreword by Alexander. Gabriel suggests we:

"find good designers - know them by their works - and study what they do"

This led later down the line to things like the Software Craftsmanship movement and op-eds like this one by Freeman Dyson extolling the union of hand and mind in making useful things. People in software had woken up to the reality that they were practicing a craft, something that was half-art and relied on skills passed down from masters to journeymen.

Why are some programmers interested in architecture? Perhaps we're working on the same problems as architects: making complex systems that people have to live with (and inside of) and adapt in the future.

We must make design choices that won't bewilder users, so that our creations can be navigated easily. Another shared problem is to work out how to make things that can be maintained over time. Systems that appear perfect and beautifully minimal can fall apart if they're constructed in the wrong way. It is usually better to make something messy with the marks of hand-crafting, something adaptable, rather than aim for outward perfection.

There turns out to be a pretty big overlap between architecture (and its problems) and software engineering (and its problems). It makes reading books from each discipline alongside each other a delight.

When I ran across these ideas in the software world years later they struck a chord of memory in me. I was very amused to find that the holy grail of certain programming greats was a book I already had on the shelf in my study for entirely different reasons. It made me feel at home in software.

So, goodbye Magic Mouse. But thanks for taking me on an lovely tour of my design and architecture bookshelf! Drop me an email if you disagree with me - does the Magic Mouse actually work for you? Have you also been influenced by A Pattern Language?

Oct 09, 2025

As promised, here are some links related to the talk I gave at PyCon UK. Thank you for being such a lovely audience. I particularly appreciate all the people who approached me after the talk to share their own experiences with Covid. It's a lonely business being ill and recovering, so it was heartening to find that it resonated with so many.

How 'long' is it?

Longer than you'd think. The NHS website explains that symptoms have to last more than 12 weeks to be counted as 'Long Covid' here in the UK.

There are a lot of people who fall in that gap. Three months is a significant time for anyone to be fatigued and feverish or to have problems with their memory and concentration, but not yet be able to access specialist advice from a Long Covid clinic. Some people will begin to spontaneously recover before they get such a referral - but they will still have been impacted and might be navigating their recovery alone. It's partly to fill in that gap that I wanted to give my talk.

Recovery over time

Fatigue and cognitive problems are common after Covid. But recovery is also common. About half of people diagnosed with Long Covid in a German study recovered spontaneously within two years, and a greater proportion saw their symptoms improve somewhat.

The study also found that if you catch Covid again it doesn't seem to affect your chances either way of recovering from any existing fatigue (hurrah!).

Aftermath

In the year after recovering from even a mild case of Covid you're about 40% more likely to develop diabetes and have an increased chance of a heart attack or a stroke.

Take care of your colleagues and watch out in particular for the signs of a stroke (act FAST!) and for the different symptoms of a heart attack in women.

I wound up with insomnia for quite a while afterwards, which turns out to be surprisingly common especially in younger people. Watch out for worsening or new-onset anxiety or depression, too, as these can also be triggered by Covid and need their own treatment.

Things that may help

When I was initially planning this talk, I filled a whole section with lots of very specific advice such as the exact type of anti-inflammatory I took, or details of a speculative treatment that my friend is trying with some success.

But when editing, I cut out those parts. I think that for me to give detailed advice is unhelpful and I'd be at risk of turning myself into one of the very quacks I warned against. Full evidence is not yet in for most things, and the high proportion of spontaneous recoveries mean it's hard to pin down things that definitely help. If you are struggling your best course of action is to find a sympathetic GP or occupational therapist, preferably get referred to a Long Covid clinic, and work with them on your specific health challenges. I am not a medical professional!

That said, there are two general tips I still want to pass along: on pacing and on sunlight.

Pacing

I always wanted to be an astronaut. Who knew I would end up having something in common with them?

Astronauts who return to Earth after a long period in space experience something called deconditioning. After the weightlessness of space their muscles have wasted away and it's hard for them to build their strength back up. Ordinary actions become more difficult. The same thing happens to people who have had a long period in bed, especially the elderly. When you've had to rest during a longer illness it's important to very gently get back into physical activity and not overdo it.

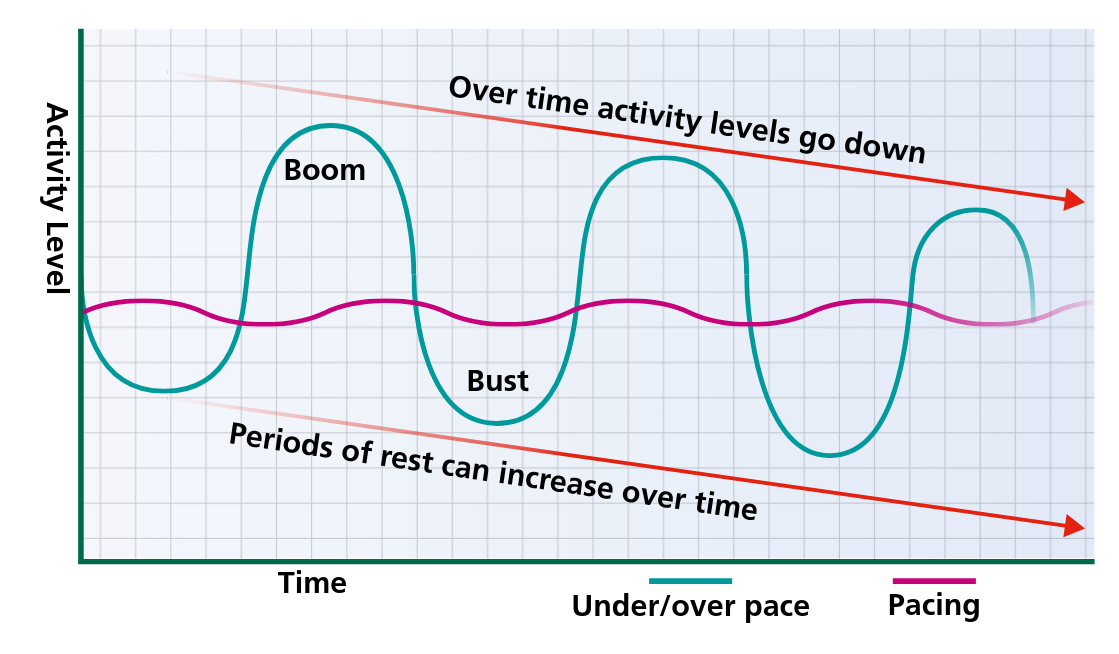

Post-exertional fatigue is a bit different than deconditioning; it doesn't hit you as you're exercising but after a time lag of an hour to a few days. You can struggle with both at the same time. This semi-scientific graph from NHS Bradford Hospitals Trust illustrates the problem:

Everyone has better days and worse days when dealing with a chronic illness. If you do too much on the better days, post-exertional fatigue will limit your activity on following days. There can be a vicious cycle of trying to get more done when you're feeling a little brighter, followed by days of needing to rest more. Over time this leads to less total activity.

Pacing is a technique taught by physiotherapists. It aims to counter the vicious cycle by teaching people to budget their limited energy and plan out their days.

This guide to pacing from the Royal College of Occupational Therapists is very useful. It describes in good detail some of the methods you can use to reduce physical and mental energy use and pace yourself throughout the day. It breaks down ordinary tasks into smaller pieces and has helpful examples of how to build rest periods into your day.

It is not a cure. A famous and vivid story about how pacing feels from the inside is the spoon theory by Christine Miserandino.

Be wary of following advice from anyone who is not a physiotherapist or occupational therapist. Post-exertional malaise is poorly understood and it is very tempting to treat it as something that you should just be able to snap out of with enough willpower. Even GPs can fall prey to these disproved ideas - they may have trained quite a while ago, with only a few hours total on this kind of fatigue.

Some of the strongest-willed friends I have are still dealing with Long Covid fatigue. If anyone could will their way past it, they could - but their bodies refuse to obey them.

Sunlight

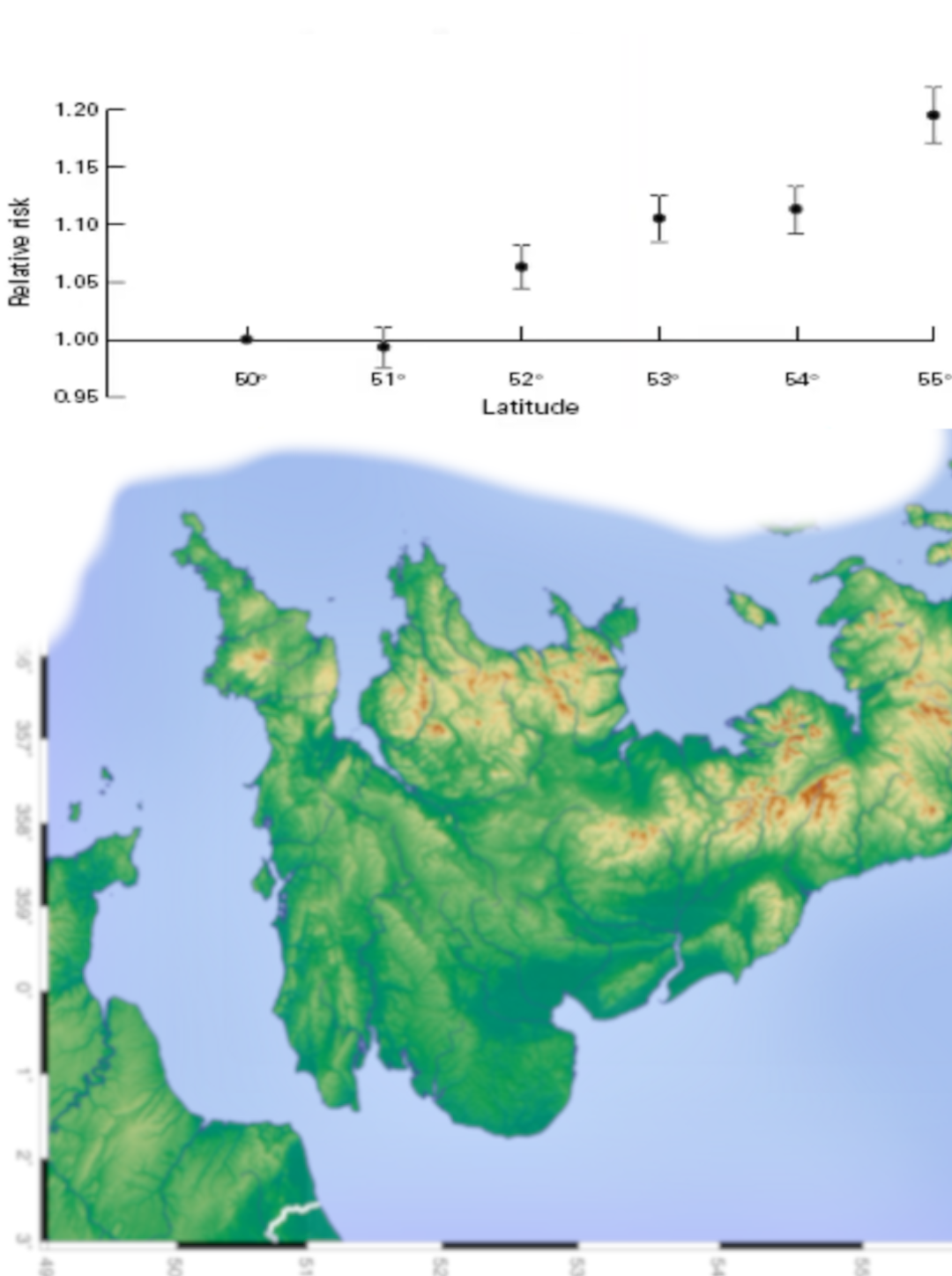

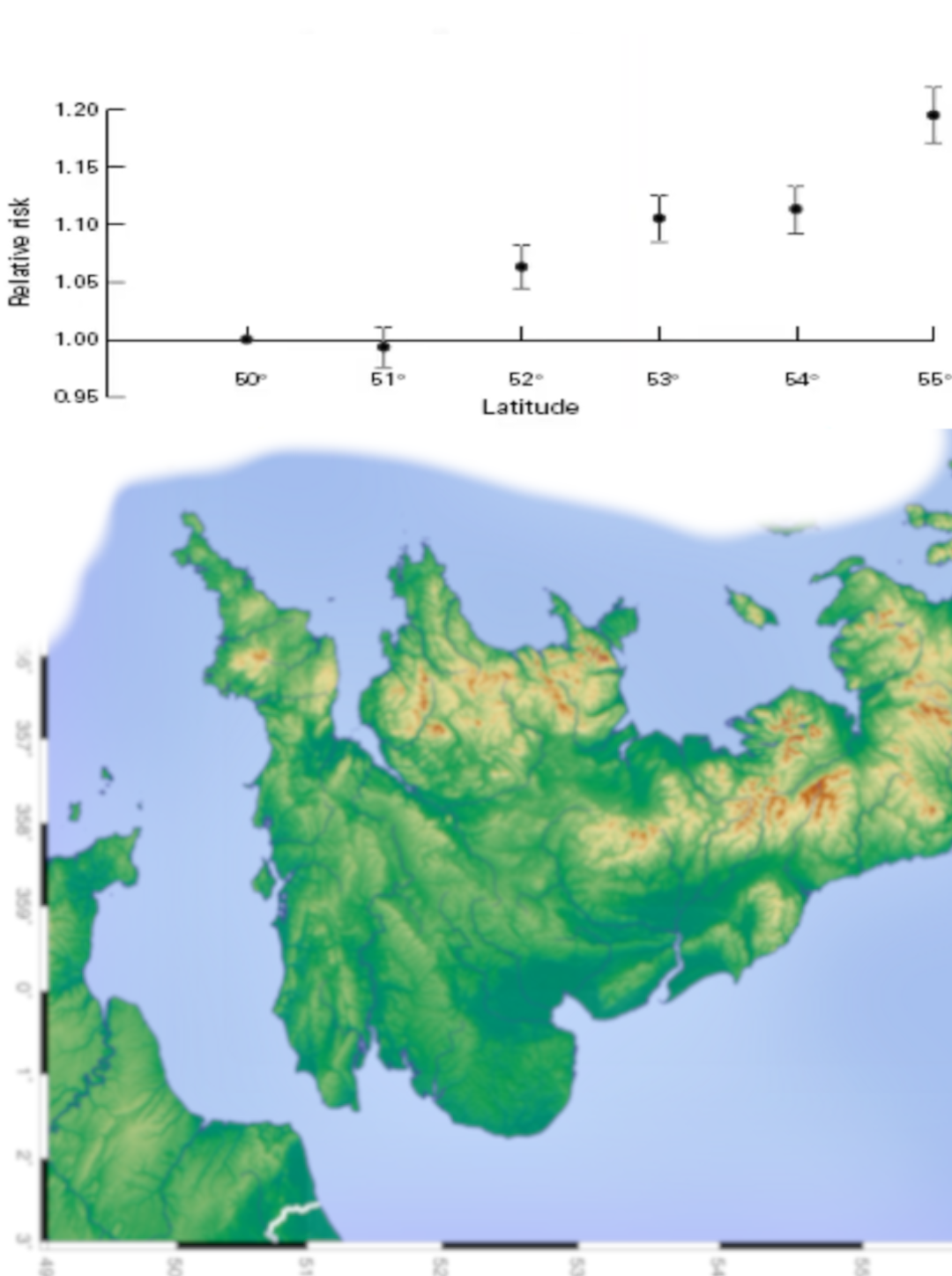

There is a link between latitude in the UK and health - the further north you go, the higher all-cause mortality rises. There are a lot of possible factors that might be behind this. But even when you control for the UK's obvious north-south wealth divide, there still seems to be something else at work here.

Dr Richard Weller, a dermatologist, has a fascinating talk 'Why Are Scots So Sick' where he lays out his theory that this is because sunlight exposure does something helpful in the skin. Specifically, he thinks UVA rays release stores of Nitric Oxide and that this helps to lower blood pressure on a population level. The further south you go, the more sunlight you can get, so the better heart health you might have.

Blue and green spaces are good for our health in other ways but this suggests sitting outside in the sunshine might be particularly helpful - not just supplementing vitamin D. Anecdotally, I always find I can concentrate better after a good spell in the sun.

Where are the new cases concentrated?

Long Covid cases are not evenly distributed. So who is suffering the brunt of Covid, and why? There seems to be a pretty clear tie to deprivation.

I made a map out of the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 data for Local Authorities (with Python, of course!)

The Geographic Data Service has a much better one broken down by Lower Super Output Area. Each LSOA is a combination of a few postcodes with perhaps 1000-3000 people total, so it's a really fine-grained look at neighbourhoods.

The Office for National Statistics data shows that in England at the height of the pandemic, the age-standardised mortality rate for deaths involving COVID-19 in the most deprived areas was more than double the mortality rate in the least deprived areas. Poverty leads to worse health and deprived areas tend to remain that way across generations, trapping people in cycles of inequality.

It might be why Covid has vanished from some fortunate people's personal radar - different parts of the country and even streets within the same city will have had different experiences with the disease.

What to take away

Do consider another covid vaccination to boost your immunity. In the UK this is covered for free for the elderly, immunocompromised and anyone else whose doctor recommends it. You can get it at the same time as your seasonal flu jab. It is also now available privately and regularly updated to defend against the newer strains.

Consider masking during high risk occasions such as conferences or other large gatherings of people where a lot of time is spent indoors - I noticed a few fellow attendees at PyCon UK chose to mask up and I'm glad the organisers made mask-friendly policies explicit.

Keep an eye on Covid cases nearby to get a better understanding of what is happening. We now have the UKHSA dashboard for public health data which tracks Covid cases (and several other diseases) and even breaks them down by local authority.

Set up your work environment for better health. Encourage anyone who is sick to take time off or work from home. Good ventilation at work and in schools is another important way to mitigate ongoing spread of Covid. There's evidence it can reduce the chances of developing a severe case if you do get infected. If you're in a position of authority at work then you can use it to help put these things in place for your colleagues - you will all benefit. Don't ever be embarrassed to ask to meet outside or in a less crowded environment, to turn up the air conditioning or open a window for fresh air.

Keep lateral-flow tests at home and test yourself if you get sick. I wouldn't have been certain or been able to prove I was suffering from Long Covid if I hadn't taken a test earlier. Some NHS foundations will not treat you for Long Covid if you haven't tested, or will continue for much longer to try to rule out other issues that can cause fatigue. Any leftover tests that the government sent you during the pandemic are probably expired, so make sure you have a fresh one on hand.

If you do test positive, try to give yourself grace and allow a longer recovery time than you'd prefer. Rushing back to work might accelerate fatigue and mean needing more time off in the long run. Pace yourself.

And remember you are not alone.

Sep 01, 2025

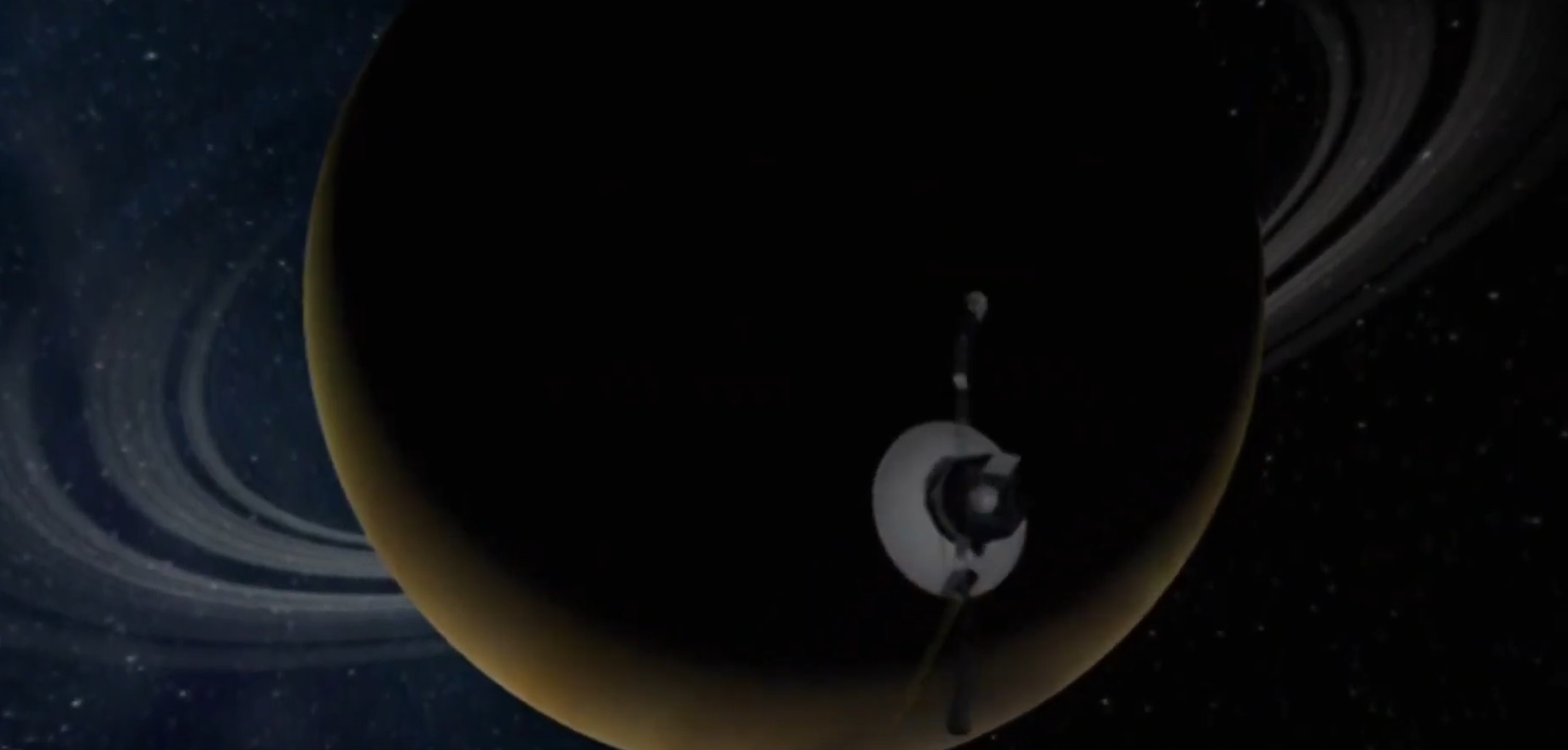

Watch the video on YouTube

This year marks the 48th anniversary of the launch of the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes. To celebrate their epic journey through the solar system and to honour the people behind the spacecraft - especially the software engineers - I made this little video. Hat tip to open-source tool kdenlive which I used to edit it.

I particularly recommend the BBC documentary 'Voyage to the Final Frontier', which goes into detail on the problems the engineers had to contend with, and how they managed to fix them from so far away. The song is 'Olalla' by Blanco White.

Jun 12, 2025

I remember reading this one a while ago when I first acted as Scrum Master for an Agile team and finding it really useful. I thought I'd revisit it to see how it holds up.

Overall Impressions

I'm still impressed by the breadth and depth of coverage the book manages - while keeping your attention with frequent vivid stories depicting how teams trying to use Agile can trip up or experience problems. It manages to give a quick but thorough run-down of general Agile principles and then a whistle-stop tour through the most commonly used Agile methodologies, comparing them and examining what the experience of teams using these techniques might look like, day to day. I think the book was a great grounding for me when I was new to the world of Agile, but I also appreciate the insights I can glean from it now after more experience. The anecdotes definitely ring true and are one of the best parts of the book - they remind me of a 'business novel' like The Goal, with characters who you end up rooting for to learn more of the Agile principles and succeed. I could see myself and colleagues at different times in the past in quite a few of them!

Cargo Cult Agile

A concept occurred to me while reading the book (I'm sure I'm not the first to think of it). It covers a lot of the sorts of situations explored in the book. Richard Feynman memorably described 'Cargo Cult Science' in a speech at Caltech:

" In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land."

In the same fashion, there are many examples of what I'd call 'Cargo Cult Agile' - companies that appear to have implemented Agile, that claim to practice it - but if you dig down below the surface and observe their actual practices (and results) you must conclude that they are not really practicing Agile. In the best cases, they have taken a lot of Agile ideas and good practices and are using them to help their business - but haven't committed to all parts of a technique or methodology ('Scrum-But'). At worst, they've just renamed their existing business processes to make them sound more Agile.

For instance, a lot of software businesses run a daily stand-up meeting for each team. Perhaps they do this because they've heard it's a good idea, or it might be that it's embarrassing not to, these days. But if you were to be a fly on the wall at that meeting you might find it's devolved into a daily status report to a boss, or that not everyone gets a chance to speak, or that it drags on for far longer than a stand-up should and everyone's sitting down because their legs get exhausted. Likewise, I'm sure that many people share the experience of being on a team that's pressed for time, on a tight deadline imposed from above, and begins to throw Agile practices by the wayside. If practicing Scrum, it feels as if there's not enough time to perform some of the Scrum ceremonies, so we won't do a Sprint Review this month, or we won't plan the next Sprint right away but just launch into doing things. But in reality every technique that's dropped leaves you less in control of your project's trajectory, stuck firefighting and unable to surface long enough to focus on what's really important.

The business stories in the book dig into this sort of situation and explore how and why it can come to be. The Scrum concept of 'Scrum-But' fits in well with a lot of the anecdotes in the book - ie when someone describes their Agile practice as 'Scrum, but we don't do xyz'. Sometimes everyone gets tired and lapses into a less effective way of doing things, but the most insidious is when a company have tried to adopt Agile, because they hear it's best practice, but don't really want to change the way they do things. So they neglect or ignore the parts of Agile that threaten the way they already operate.

The worst part of Cargo Cult Agile is that it leaves the impression on people - particularly graduates who don't have a wide experience - that this is what Agile means. They're often left with a lasting distaste for the labels of concepts that are supposed to help energise and jell a team. If your regular 'stand-up' meeting lasted 45 minutes and you often didn't get the chance to speak because it was dominated by senior engineers discussing issues with each other in depth as you leant against the wall and tried to stifle your yawns ... you're not going to be keen on going to stand-up meetings in future. And if you become a senior engineer, perhaps you'll feel it's OK to dominate Stand Ups with your longwinded technical discussions, since that's how you learned about the idea of a stand-up. This is not good for our discipline's professionalism.

There are valiant attempts to fight these tendencies by Agile practicioners worldwide. Training offered by the Scrum Alliance attempts to put the practice of Scrum in particular on a more professional footing, and it's a good sign when a company sends its employees on Certified Scrum Master training as a matter of course - it means they are more likely to have some form of committment to Agile. But there can still be a large disconnect - a chasm - between the ideals that someone learns on a training course, and the reality they experience when they return to the office.

Another avenue through which Agile can get more successful adoption is hiring Agile coaches to work alongside teams for weeks or months and coach them in the practices and techniques of Agile in person. These folks have a daunting job indeed. Not only do they have to convince the cynical programmers that they're working alongside that this management fad (for they will have lived through many) will actually make a positive difference to their work lives - they also have to convince top management that it is worthwhile. Often, organisations will have lived through multiple unsuccessful attempts at transforming software delivery into an Agile process. The pinnacle of success in Agile adoption is always fragile. It only takes a little more institutional inertia, a little more doubt from management to reverse such a transformation entirely.

Fundamentally at odds

It's easy to pick up a simplistic idea of Agile, but hard to put the principles into practice, because they involve things that management in particular is uncomfortable with - giving up control to the development team, not knowing in advance all the details of what will be made, trusting the people who will do the work to estimate the time it will take. As Thomas Lindquist points out, fundamentally what's going on here is a collision between the egalitarian values of Agile with the typical command-and-control corporate structure.

"The hard truth is that Agile and Traditional Management still don’t get along. In repeated polls of people working in many different firms where Agile and Scrum are being implemented, somewhere between 70 to 90% report tension between the way Agile/Scrum teams are run in their organization and the way the rest of the organization is managed. Generally less than 10% reported 'no tension.'" Steve Denning, Is Agile Just Another Management Fad?

This is a bit of a depressing realisation, because it means these problems are baked into many organisations from the start. Those who wish to implement Agile can naturally expect resistance, a constant struggle to preserve the ideals of the methodologies against the tendencies of their own organisation, unless they are lucky enough to work for a smaller organisation or one with a more egalitarian structure (or for themselves, of course).

As Jurgen Appelo observes in the foreword to Michael Sahota's 'Agile Survival Guide' (which I highly recommend for thinking about this problem),

"People don’t struggle so much with the adoption of Agile practices. They struggle with the transformation to the Agile mindset, because many organizational cultures actively resist it."

Why do they actively resist it? Sahota compares it to T-Cells in the immune system, designed to kill foreign elements in the body (organisation). When one team makes a successful transformation to Agile ways of working, they experience a reaction from other parts of the organisation - unless they can disguise themselves as appearing to do 'business as usual'. In one of his suggestions, this takes the form of a useless Microsoft Project Plan that has no value to them or their customers but is required by the organisation for their team to work without further disturbance. Sahota suggests that Scrum is actually too powerful a tool - he points out "Scrum is designed to disrupt existing power and control structures by creating new roles (Product Owner, Scrum Master, the Team). It also posits self-organizing teams as the fundamental building block of organizations. As such, it should be avoided if at all possible" as it will inevitably cause conflict and a complete failure of Agile adoption.

What is it that makes organisations so resistant to the very techniques that would help their workers do better work, become more closely connected to customers, have more control over their working environments and thus, be happier at work? Isn't that ostensibly what corporations want for their employees? Well, not really. Outside of vapid public relations exercises, what corporations actually want is what their shareholders want: to extract a maximum of profit from the efforts of their labour force, who they regard as interchangeable Human Resources. This leads to the dark side of Agile:

"[T]he danger [is] that people outside the development team will hear these metaphors and misunderstand them — as a promise of work at a greater intensity and nothing more. Thinking that, apart from that, Agile is business as usual. Still yearning to make more money out of predictability, lower skills and lower wages. Not understanding that the point of Agile is to be Antifragile."

Is your development team stuck in this sort of situation? How did you try to mitigate it? As always, I'm interested to know your thoughts via email.

Jun 24, 2024

They also serve who only stand and watch construction

They also serve who only stand and watch construction

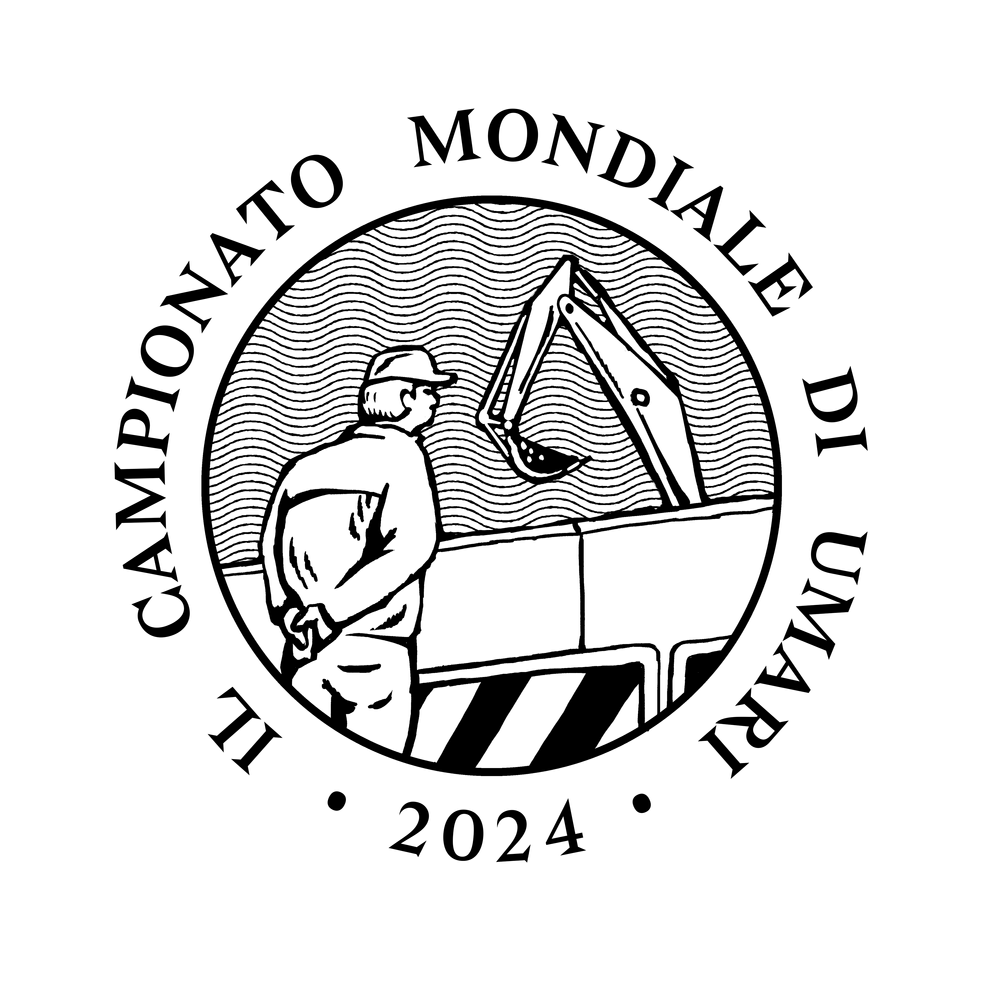

I'm delighted to say that I recently won a writing challenge, 'Il Campionato Mondiale Di Umari'.

An 'Umarell' is a lighthearted way of referring to elderly men who like to watch construction sites. The practice is apparently so common in Italy that special holes are often included in fences around roadworks to make it easier for these retired guys to enjoy their favourite pastime. But ogling construction work isn't just for retired people! Spencer Wright at Scope of Work explains -

To umarell is to take an interest in the built environment – the environment that our species creates, and in which most of us spend most of our time. An umarell turns their attention to that environment's creation, taking time to appreciate the materials, machines, and muscles from which it emerges. Umarelling is an act of respect and appreciation, and it is for this reason that I am proud to announce the inaugural Campionato Mondiale di Umari – the 2024 World Umarelling Championship.

The championship had three categories: notes, sketches and open text. I won in the open text category with an original poem and was delighted to be sent my own official 'Umarelling' notebook and a T-shirt which I'll wear with pride.

Check out my work and that of the other two winners here!

The challenge was organised by my favourite design and engineering newsletter, Scope of Work, which I've been following ever since I was an undergrad in Manufacturing Engineering. Spencer Wright's newsletter is always one of the things I look forward to most in my inbox. If you like deep dives into how we keep food fresh, the history of soap in a box, or understanding what it takes to put a flamingo inside a beachball you'll definitely enjoy Scope of Work. I can't count the number of times it's introduced me to my latest obsession.

Jun 16, 2022

I spoke at a virtual conference!

I spoke at a virtual conference!

I was recently invited to speak at Code Newbie's CodeLand 2022. I had a wonderful time at the virtual conference and got the chance to speak with some great people including experts in the field (I was part of a roundtable discussion with Kelsey Hightower, I was starstruck!). Code Newbie's community is a lovely welcoming place for everyone, especially folks who are just getting started in software professionally. I'm definitely interested to go along again next year.

If you'd like to watch my talk, it's still available on demand here

Mar 13, 2021

He's very new!

He's very new!

I won't be updating this blog for a while as my little one has finally arrived!

We're having a lot of fun (although not a lot of sleep).

May 22, 2020

Masts of the SS Richard Montgomery. Photo by Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent CC BY

Masts of the SS Richard Montgomery. Photo by Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent CC BY

I'd like to introduce you to the SS Richard Montgomery. For those who don't know the story already, it's quite extraordinary.

Towards the end of WWII, a Liberty Ship, the SS Richard Montgomery, ran aground on shifting sands just off the coast of Sheerness at the mouth of the Thames Estuary. She was loaded with over 6,000 tonnes of high-explosive bombs and detonators. Salvage operations managed to remove some of the explosives, but before the ship could be made safe it sank further and salvage was abandoned. The ship and her thousands of tonnes of remaining explosives was then left to sit for over 75 years. She is still there.

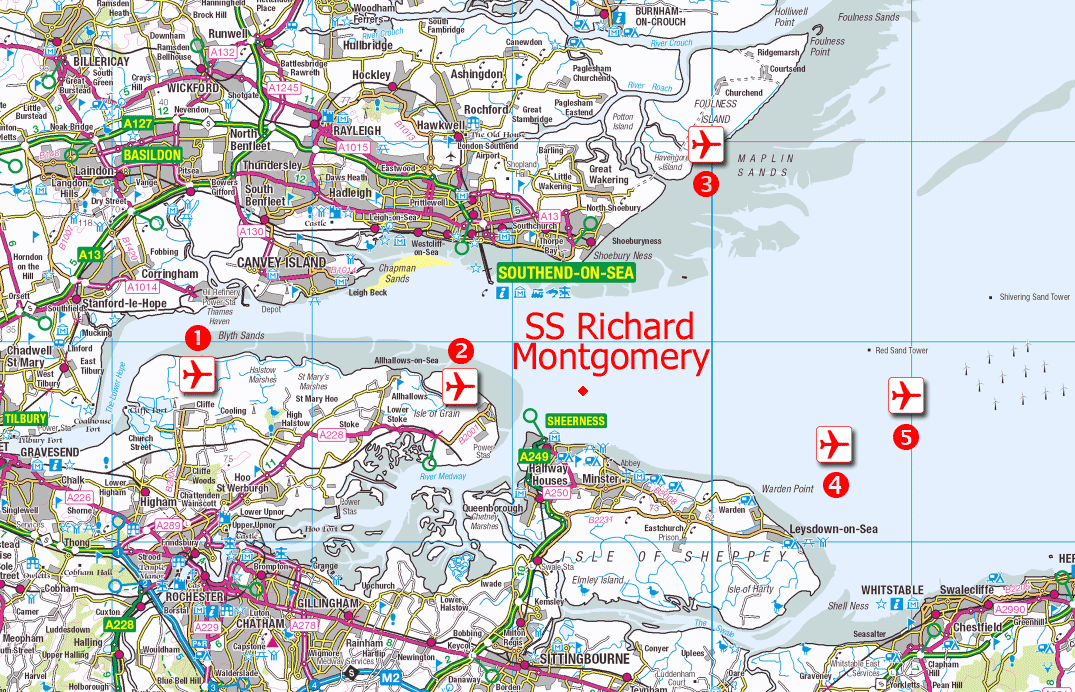

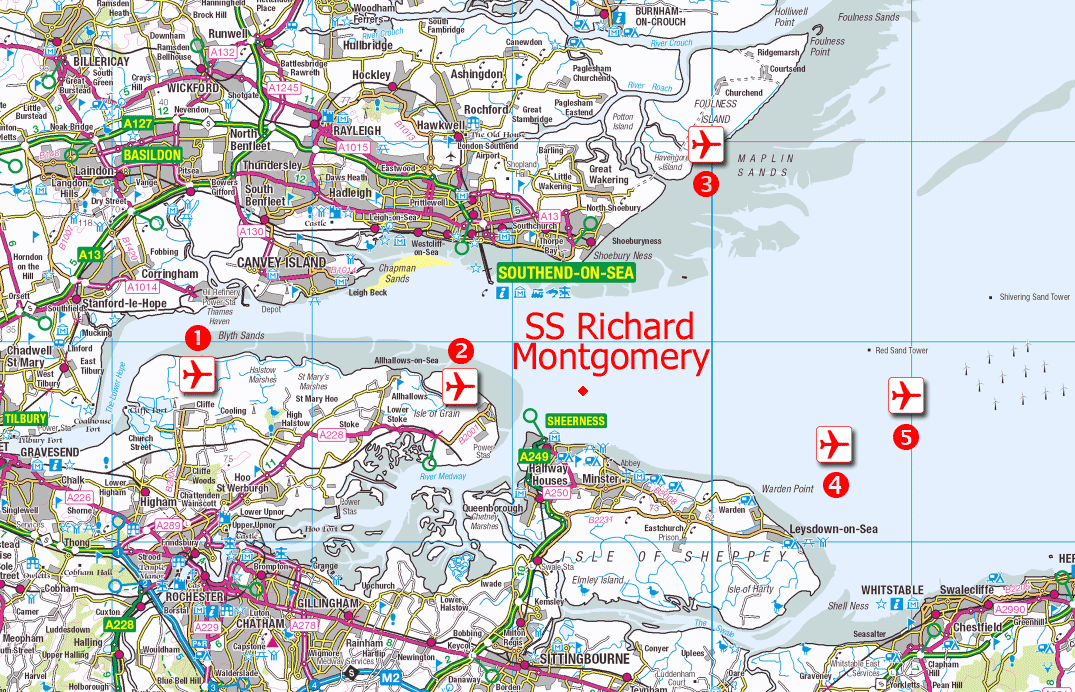

One of the most remarkable things about the wreck is her location. She lies in shallow water just 2.4 km from the seaside town of Sheerness. Not only that, but she is less than 200m from a busy shipping lane, and remarkably close to the Grain Liquid Natural Gas Terminal, the largest Liquified Natural Gas facility in Europe.

How dangerous is it?

WWII ordinance turns up every now and then during construction projects. Some unexploded WWII grenades were discovered while building an ice rink in my home town of Cambridge. The discovery triggered a visit from the bomb disposal squad and emergency services, alongside a limitation on flights in and out of Cambridge Airport until the grenades could be made safe.

But the amount of unexploded munitions here is in an entirely different category. There are no clear records of how much ordinance was left on the ship, but according to an official MCA report the ship likely contains more than 9000 explosives including cluster bombs and hundreds of giant 2,000lb 'blockbuster' bombs.It's hard to comprehend their explosive power should they go off.

A New Scientist investigation from 2004 suggests that spontaneous detonation of the entire cargo would hurl a column of debris up to 3 kilometres into the air, send a tsunami barrelling up the Thames and cause a shock wave that would damage buildings for miles around, including the liquid gas containers on the nearby Isle of Grain, which could detonate in turn.

What happens next?

Suggested locations of new airport in Thames Estuary. By Ordnance Survey with modifications by Prioryman CC BY 3.0

Suggested locations of new airport in Thames Estuary. By Ordnance Survey with modifications by Prioryman CC BY 3.0

Some demolition experts are content to let the wreck lie, hoping that time and tide will reduce the deadliness of her cargo. They argue that any attempt to clear the bombs from the wreck would be riskier than letting her lie. These arguments give the example of the explosion of the Kielce, a smaller munitions wreck which was more than 6km out to sea. A failed salvage operation there in 1967 set off an explosion that measured 4.5 on the Richter scale and damaged property in nearby Folkestone.

However, others disagree and argue that the wreck is actually becoming more dangerous over time. Phosphorous is now apparently leaking from the munitions aboard, evident as flames on the surface of the water where it burns in contact with air. These can sometimes be seen at night by local residents.

Another possibility is a collision. There have already been at least 22 near-misses where shipping traffic only just steered away from the exclusion zone around the wreck in time. One particularly harrowing episode occurred in May 1980 when a Danish chemical tanker, 'Mare Altum', steered aside only minutes before she would have impacted the Montgomery.

There have been persistent questions in Parliament asked about the subject. Recent surveys suggest that the condition of the wreck is rapidly deteriorating, which might lead to a sudden catastrophic collapse. Dave Welch, a former Royal Navy bomb disposal expert, who has advised the government on the SS Richard Montgomery's munitions, says:

"We can’t continue just leaving the wreck to fall apart. Somebody at some point in the next five to ten years is going to have a very difficult decision to make and I would say the sooner it’s made, the easier and cheaper it will be as a solution."

So far, no solution is in sight.

How does this relate to programming, anyway?

Every codebase has its unexploded bombs. Not so potentially serious as the SS Richard Montgomery, perhaps. But our code is out there driving all sorts of things in the real world. If we neglect potentially serious problems, we can harm people just as easily as other kinds of engineers.

Take your bug reports seriously

It can be too easy to dismiss user reports of bugs or accidental misuses of your application. Because we are so familiar with our own code, it can lead to a feeling of contempt for the person who doesn't approach the software in the same way that we do, or have as much knowledge about the underlying structure. And there is of course a natural feeling of defensiveness toward our own work. It can be humbling to find a bug in what you had hoped was well-crafted code, a blow to your ego and confidence as a programmer, perhaps.

This kind of misplaced confidence can be lethal. In the Therac-25 Incidents at least 6 cancer patients were given hundreds of times the desired dose of radiation therapy. This resulted in serious injuries and deaths. The malfunctions were reported early to the manufacturer, who sent engineers to a hospital where one of the lethal accidents occurred. They spent a day running the machine through tests but could not reproduce the critical malfuction, code 54, which only appeared when users typed with a certain fast frequency as experienced operators sometimes could. Because the error that caused the lethal bug was not observed by company investigators, they concluded it was "not possible for the Therac-25 to overdose a patient". It took another tragic accidental death to prove them wrong. This excellent analysis of the accidents dissects the timeline of events and has valuable lessons for us, particularly medical software developers.

We can be falsely confident about our code fixes, too, thinking that they resolve an issue when really they don't. It takes a particular critical, persistent mindset to debug a system well and really fix what the root of a problem was. The excellent rules of thumb in Dave Agans' 'Debugging' book are something I return to time and again when tackling software problems. I encourage you to print out the poster and put it on your wall! One of his key points is that until you can reliably trigger a bug, you don't know what the true cause is or whether a fix has addressed the bug or not. Intermittent faults which only appear under certain conditions, like the problems with Therac-25, can be the hardest things to address.

Listen to the voice of inexperience

Listen to newcomers - interns, new starters, people approaching a piece of the code they haven't worked on before. It's very easy to become habituated to a worrying situation - to live atop an unexploded bomb - and sometimes the only way to snap out of your ingrained habit of dismissing a problem is to listen to someone new worry about it.

I would argue that part of the onboarding process for programmers joining a new team should be to ask them what 'unexploded bombs' they might see in the code. There's usually a "and do you have any questions for us" stage in an internship check-in, for instance, but we rarely take the feedback we recieve this way seriously, or get enough detail to understand what about the codebase might be confusing or painful to work with.

Doing a 'Code Walk' structured walkthrough of the code can be very illuminating. (I highly recommend this talk by Mary Chester-Kadwell - it has really shaped the way I teach and learn about new codebases). In the process, pay attention to the questions your new team-mate asks and reflect on what they say about the health of the different parts of your codebase. Is there anything where when you explain it aloud, it seems convoluted and awkward, or counter-intuitive? Anywhere you particularly wish there was documentation to show your new recruit? Those places may be where problems are lurking.

Pay attention to the jokes

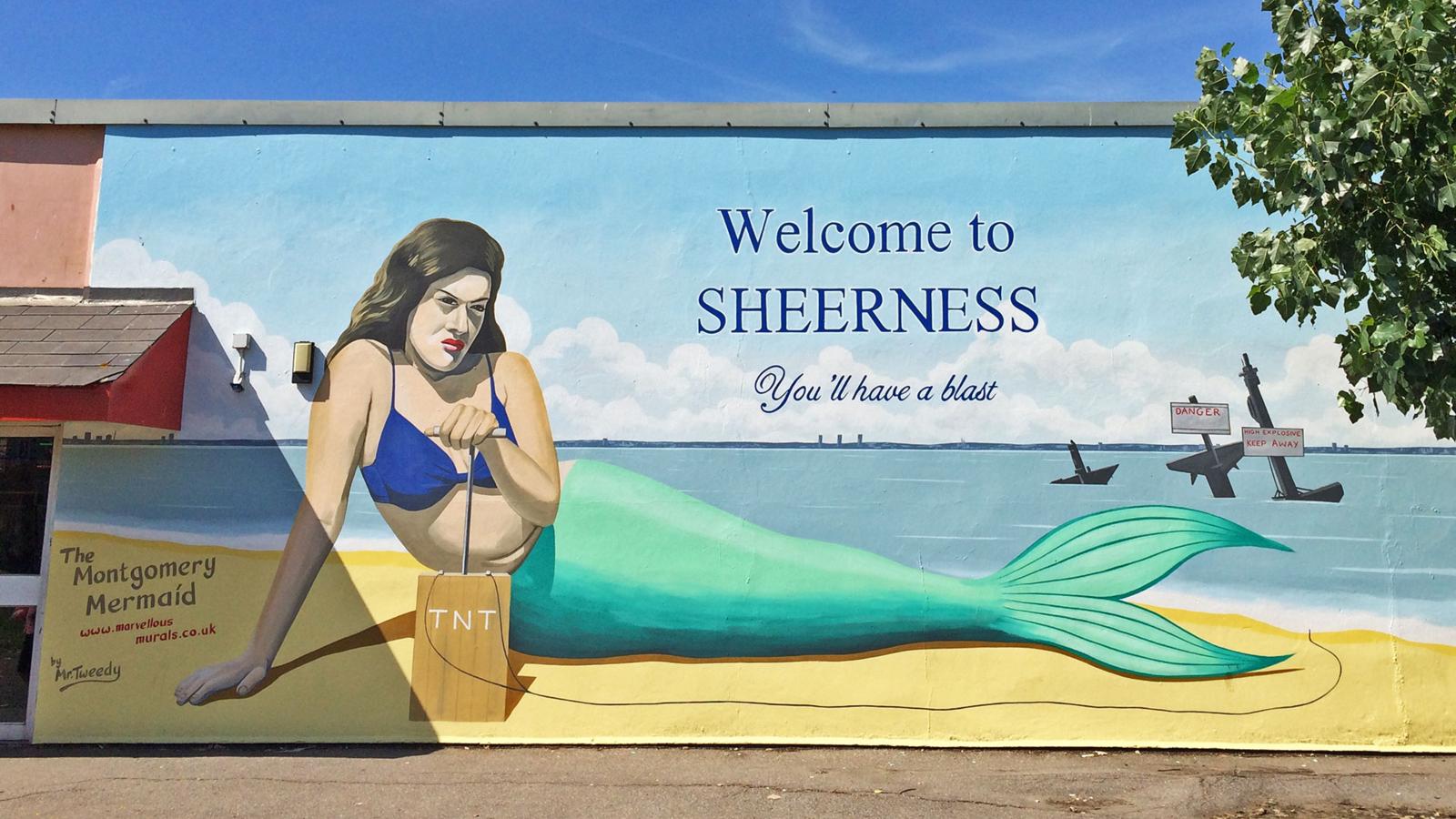

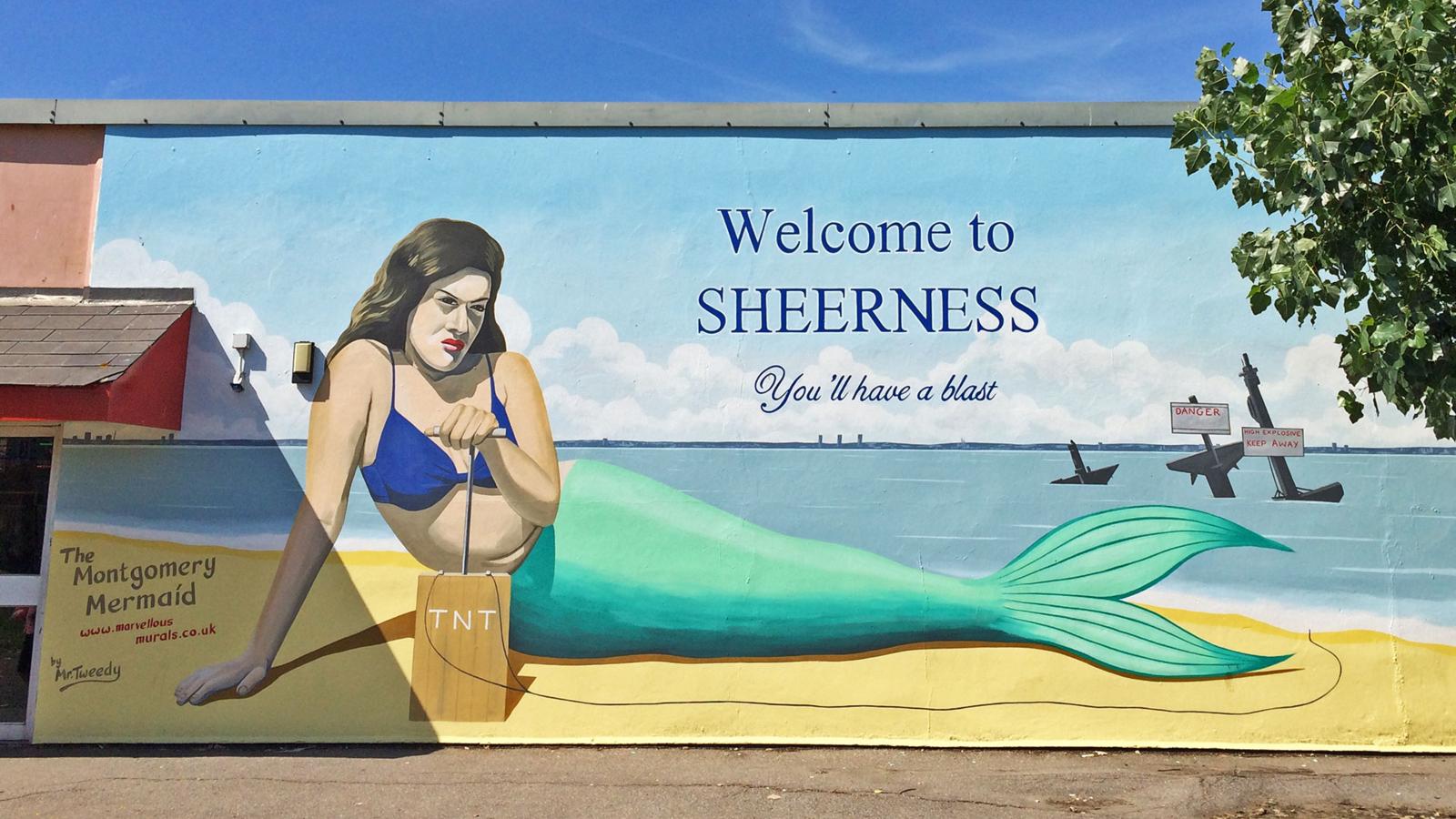

Mural by Dean Tweedy made for the Promenade Arts Festival in 2015 - photo Andy Hebden

Mural by Dean Tweedy made for the Promenade Arts Festival in 2015 - photo Andy Hebden

Matt Brown, chairman of Sheerness Enhancement Association for Leisure, condemned the mural in the local newspaper, saying:

"If I was a family visiting, whether I knew about the Montgomery or not, I wouldn’t want to be sitting at the leisure park with the kids being reminded you have those explosives out there."

The artist rebutted: "I wanted to make people aware of the Montgomery as it’s part of Sheerness. Some people would like to deny its existence."

The mermaid makes some local people uncomfortable because it reveals a truth about their town they'd rather not have to acknowledge - the ever-present danger to their lives from the offshore explosives. For a certain kind of authority figure, the reminder of a dangerous situation is worse than the actual danger, because without the reminder they can continue to live their lives without having to address the elephant in the room.

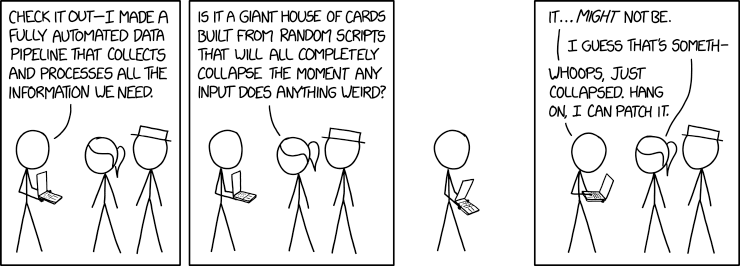

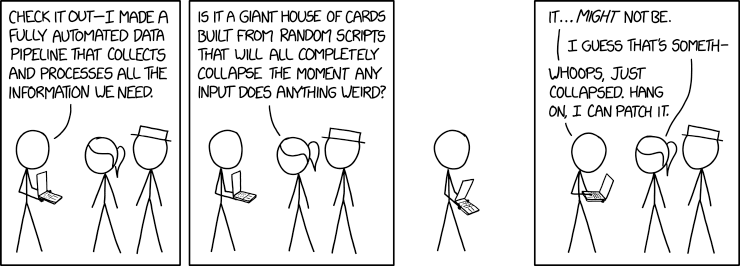

This xkcd strip about data pipelines makes me laugh - but it also makes me think about the robustness of my code.

This xkcd strip about data pipelines makes me laugh - but it also makes me think about the robustness of my code.

Sometimes the equivalent of a Sheerness Mermaid Mural is the only way you can spot a problem that's become engrained in the way your code is put together. Is there a particular XKCD or Dilbert cartoon that seems to epitomise the bugs and problems you're encountering? Perhaps all the developers working on a particular part of the codebase have a set of in-jokes describing the way a certain class behaves itself? A kind of gallows humour about how a module is annoying to use, something that makes you cringe because it's a little too accurate?

These are all clues to what might be underlying dysfunctions of your code. By paying attention to them, you might be able to spot an unexploded bomb and defuse it, before your users discover it and blow things sky-high.

Sep 16, 2019

This is a write-up of a workshop I've given at CamPUG and PyCon UK 2019. It was a lot of fun to deliver, and my participants came away with their own mini-games written in Ren'Py. I was impressed by the range of creative stories, everything from getting lost in Cardiff, storming Area 51, coaxing a grumpy cat, visiting a music festival, going to space, defeating animated fleas, visiting every pub in Cambridge, a child's guide to the Divine Right of Kings, interactive graffiti and more!

I hope this post will be useful as a reference for workshop participants and those who couldn't make it along.

What is Interactive Fiction?

You might be familiar with the concept of interactive fiction from "Choose Your Own Adventure" books.

Ever since computers came on the scene there has been interactive fiction here, too. Zork, one of the earliest examples, is a dungeon-crawling game where the player explores The Great Underground Empire by typing text commands.

Using later tools like Parchment and Twine people are still creating these text-based interactive fiction games. A text-based game I've enjoyed recently is Moonlit Tower by sci-fi author Yoon Ha Lee.

Visual Novels are a genre of interactive fiction that combines pictures and text as a storytelling tool. They originated in Japan and many famous examples such as Fate/Stay Night and Symphonic Rain are Japanese. These games are often romance or relationship-themed, each path perhaps leading to a relationship with a different character.

Ren'Py

Ren'Py is a visual novel creation engine written in Python. It has its own syntax and style, but also allows you to embed pure Python for more complex gameplay mechanics.

It is cross-platform and works on Mac, Linux and Windows. All that you need alongside it is a simple text editor that can convert tabs to spaces, such as gedit.

What can you do in Ren'Py?

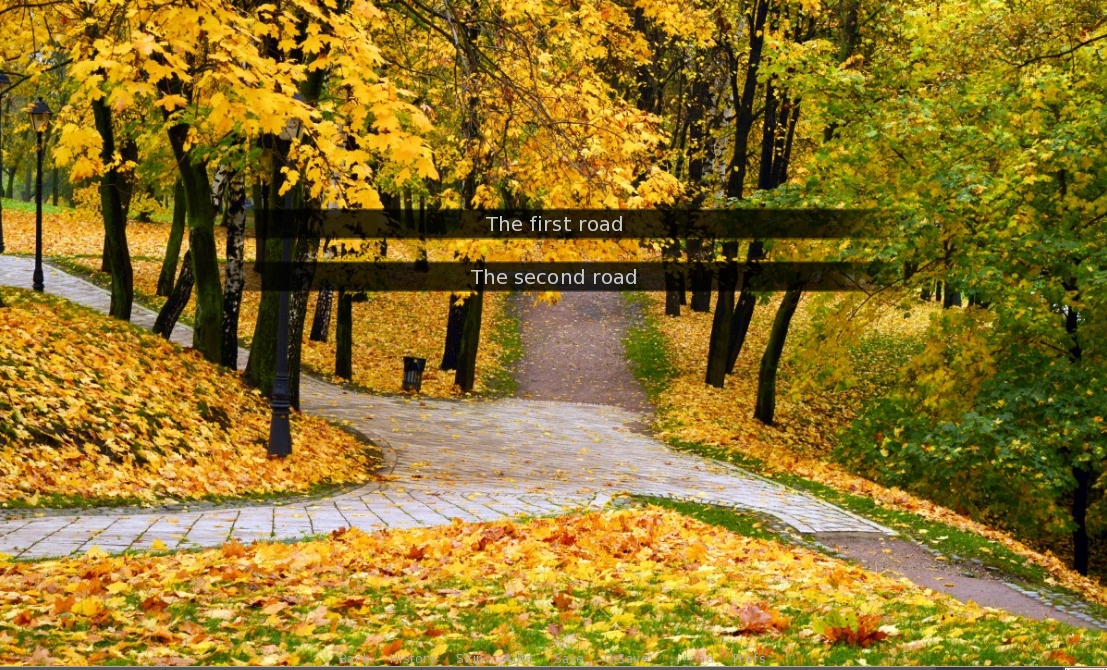

Label Jump For Branching Stories

I would humbly suggest my own game The Road Not Taken as a useful introduction to the label / jump mechanic. Take a look in the script.rpy file to follow how the game works. It demonstrates how menus work in the game and how you can use them to move to different choices, similar to a GOTO statement. It also includes an example of embedding music within gameplay to add a mood to a scene. Feel free to copy and modify it as a basis for your own games.

Custom GUI

Hotel Shower Knob, a game where you have to puzzle out an unfamiliar hotel bathroom to take a shower, is a good example of a custom GUI. Inside options.rpy the creator replaced the usual cursor with a custom image of a hand:

## The mouse clicker thingy.

define config.mouse = { 'default' : [ ('cursor.png', 66, 95)] }

This makes for a unique visual experience. As the hand is Creative-Commons licenced, you could use it in your own games, too!

Embedded Python

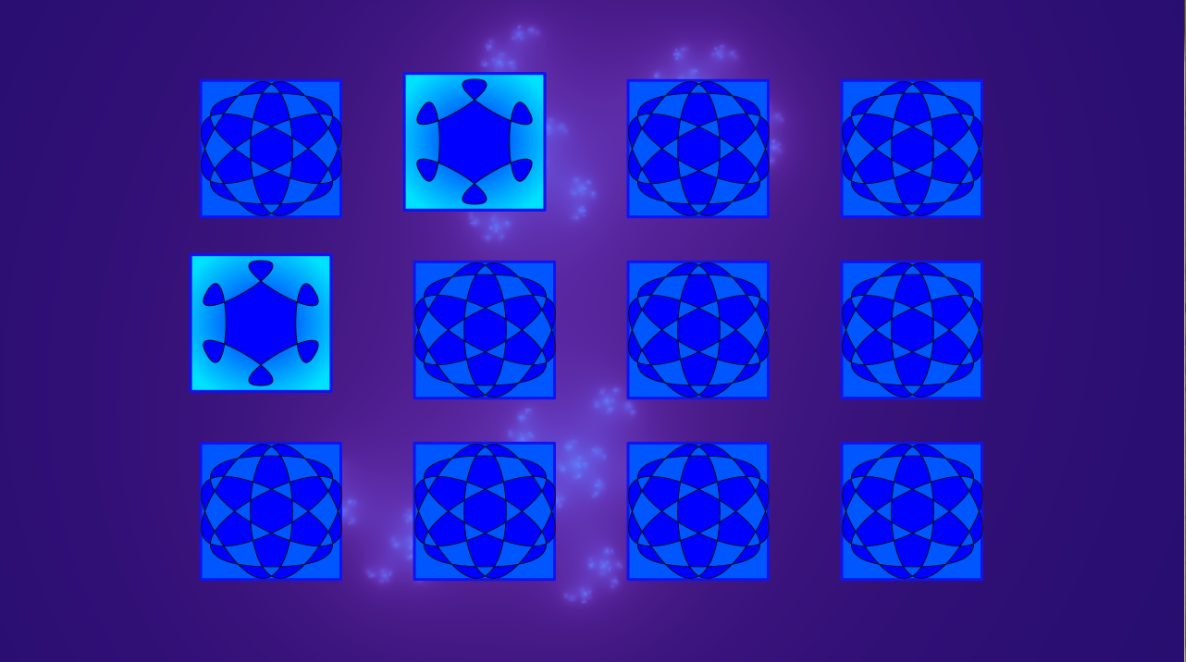

Because Ren'Py is written in Python (2.7, if you're interested) it's easy to embed Python statements within it to acheive more complex effects such as creating mini-games. There are two ways to do this - prefixing single lines with $ or using an indented block with the python: statement. I used python: statements within Ren'Py to create Card objects for my game Two Worlds.

The key thing to notice is the definition of the Card class:

# Define the card objects used to play the games with

init:

python:

flowers = ["card-front-land-flower%d.png" % i for i in range(1, 3)]

class Card(object):

def __init__(self):

self.face_up = False

self.selected = False

self.number = 0

self.coords = [0, 0]

self.back = "card-back-land.png"

self.front = flowers[0]

self.paired = False

@property

def coord_text(self):

return "{}, {}".format(self.coords[0], self.coords[1])

This happens during the init: block, before the game starts, so it is available from the beginning. I subsequently used this in the sea_game.rpy and land_game.rpy files using the ui.interact() statement and action If to connect it with Ren'Py responses to on-screen clicks.

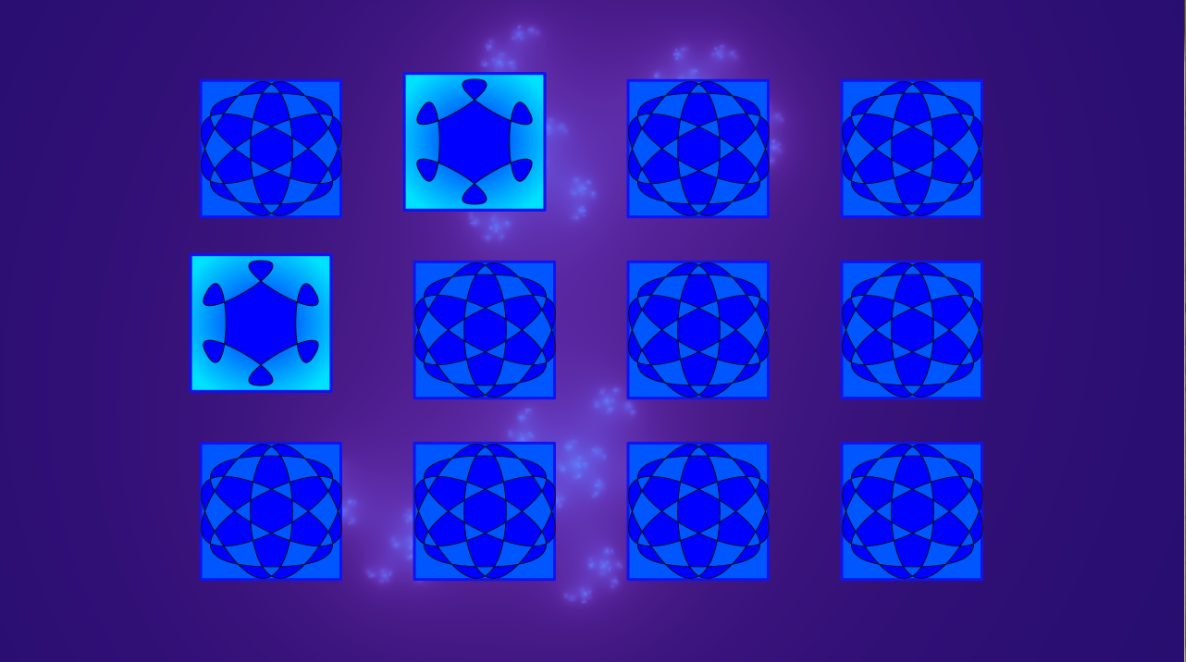

Persistent Data

Another useful trick is the ability to store persistent data between plays of the game.

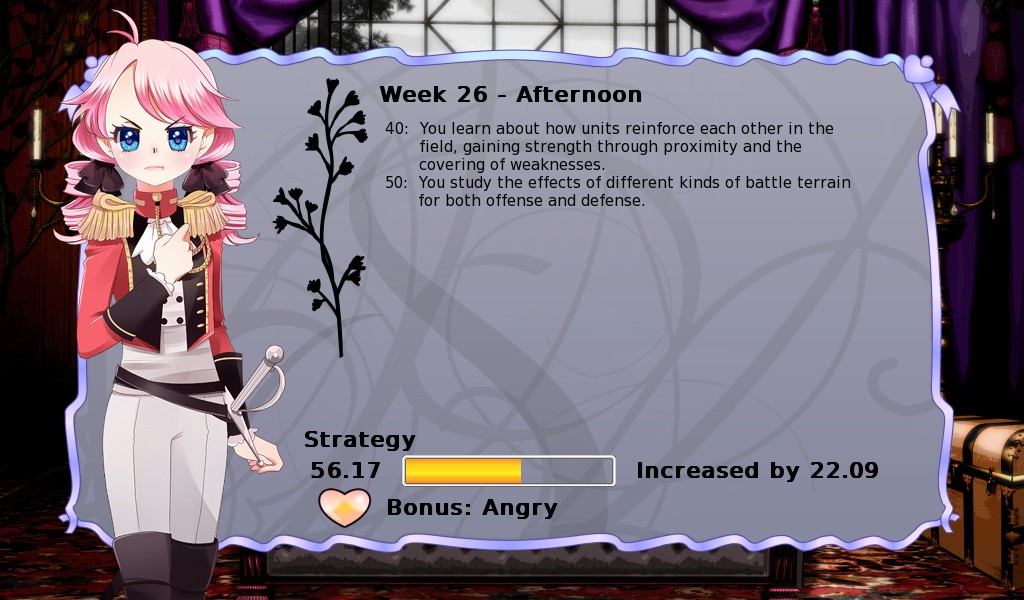

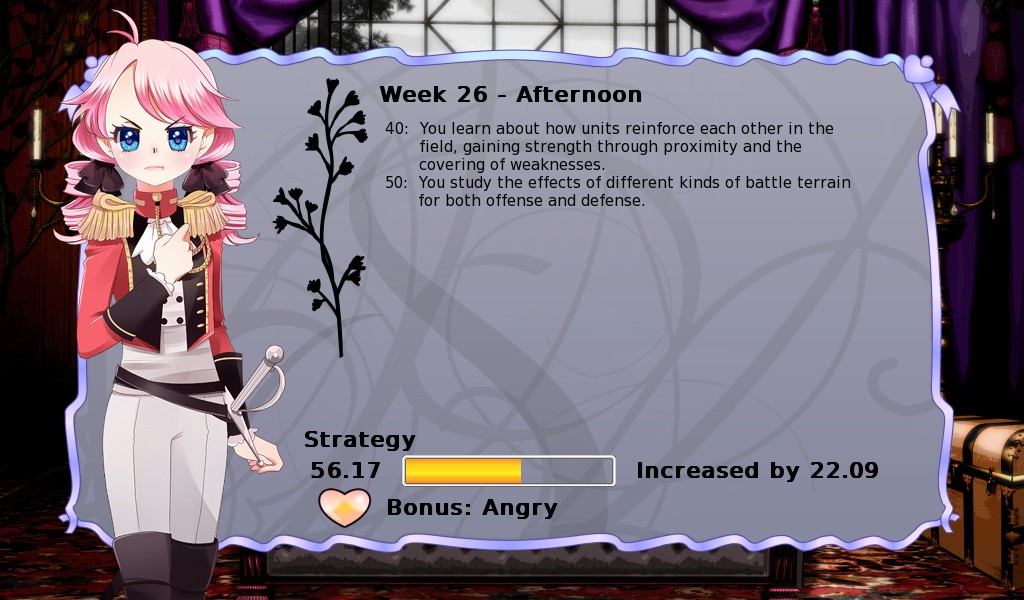

An example from Long Live The Queen

An example from Long Live The Queen

This allows more satisfying gameplay such as unlocking new routes after a complete playthrough, and keeping track of player stats like Strength or Skill. Anything that can be pickled is suitable for this treatment. A simple example:

if persistent.secret_unlocked:

scene secret_room

e "I see you've played before!"

To unlock this path the user must hit a piece of code that sets $persistent.secret_unlocked = True

persistent is a special keyword in Ren'Py, so you shouldn't use it for anything else. Unlike other variables, if you haven't yet initialised it when you reach the if statement Ren'Py won't complain.

Useful sources of free images and sounds for your games

There are various community projects to collect images and sound to use in games with Creative Commons or similar licences.

I've found px here a useful collection of images, particularly photos.

I used Fraqtive to create the card images and backgrounds for Two Worlds.

Useful sound sources include Free Music Archive and for sound effects, Free Sound

Example games written in Ren'Py

Benthic Love – Michaela Joffe, Sonya Hallett

Hotel Shower Knob – Yoss III

Death And Burial Of Poor Cock Robin – Lernakow

Long Live The Queen – Hanako Games

And check out the NaNoRenO game jam each year during the month of March – or better still, take part!

Apr 12, 2019

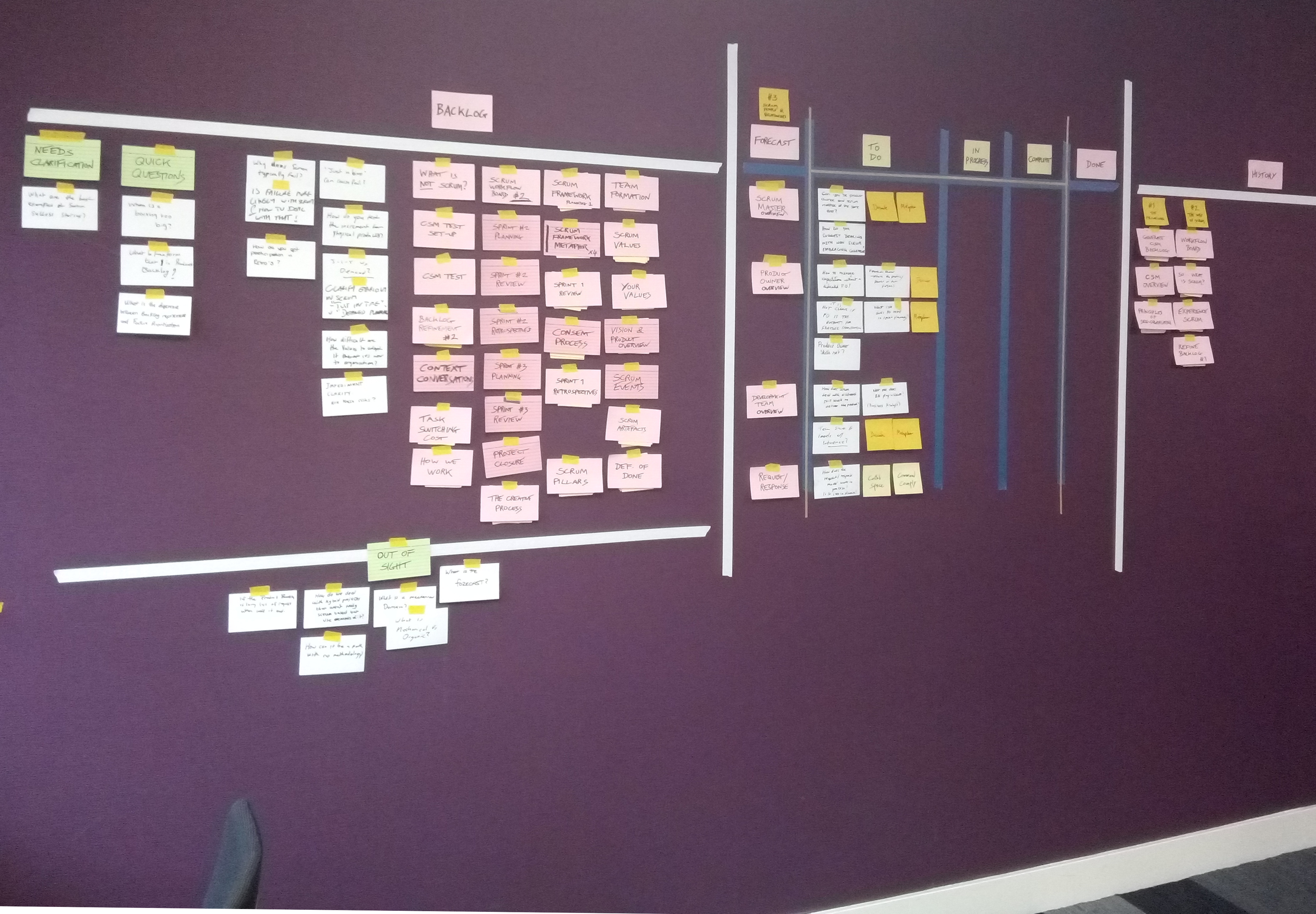

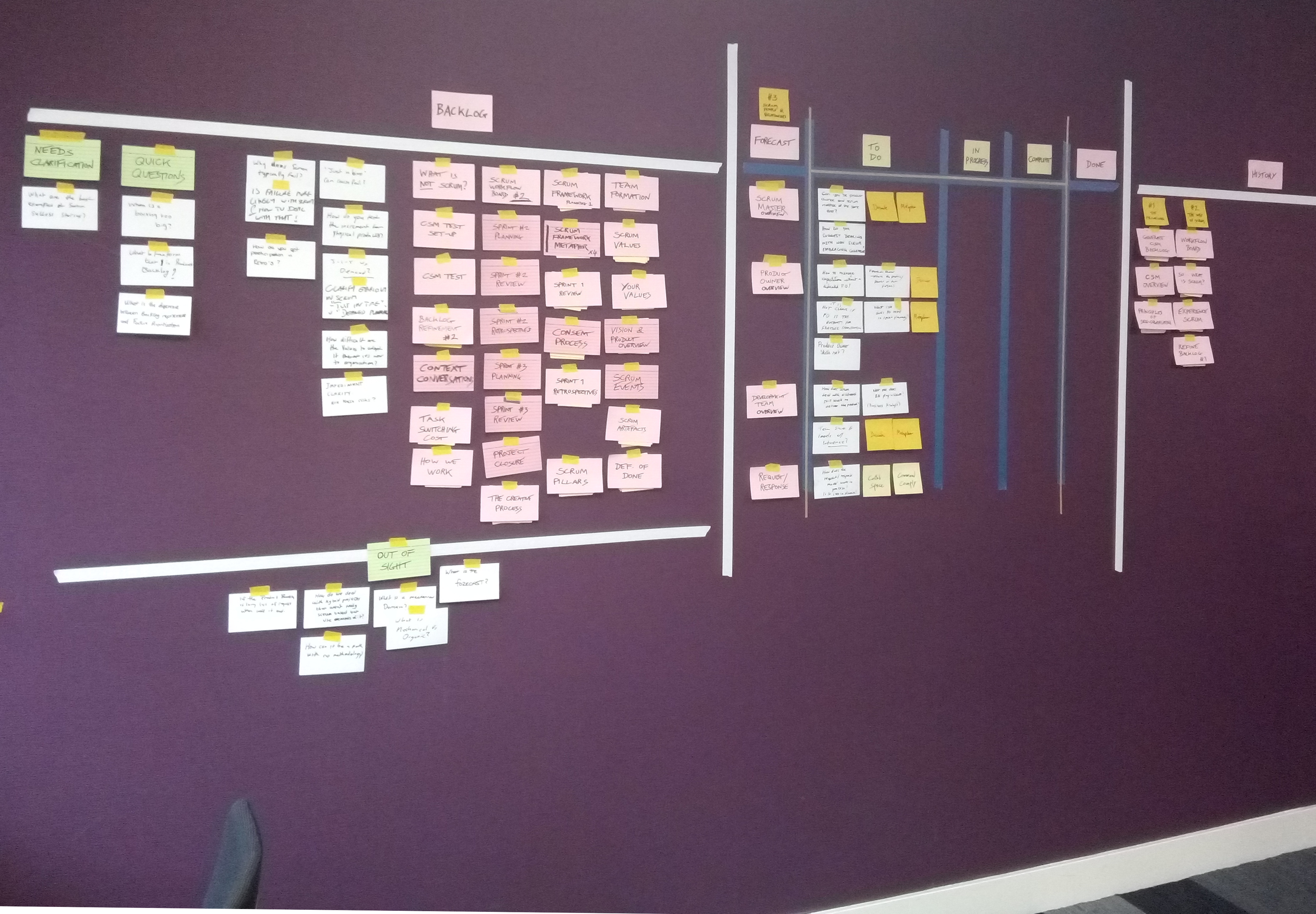

I recently attended a Certified Scrum Master course taught by Tobias Mayer of Adventures With Agile. I really enjoyed the course and the style in which it was taught. There was no death by Powerpoint! Tobias actually constructed a board on the wall with columns to keep track of the tasks comprising the course, and we added extra task cards for further discussion and questions as we went along.

Here's what the board looked like near the start of the two day course.

Here's what the board looked like near the start of the two day course.

We held 'Sprints' of an hour or so at a time, diving into aspects of Agile and then reviewing how it went, to improve our group process. Sometimes the teacher would stand and talk about a concept for a while, but mostly the course was interactive, especially during the second day where we broke out into groups for longer sessions.

The exercises we did included 'Point and Go': a game where players stand in a circle and have to

- Point to someone else whose place you want to take

- Wait for them to say "Go"

- Start moving forwards to them

- Before you reach them, they have to find another place to go (and the cycle continues!)

This was unexpectedly hard! It was a metaphor for how difficult it can be to break out of an established pattern of behaviour at work. Even once we got into a rhythm, if things sped up or someone panicked, our orderly pattern fell apart.

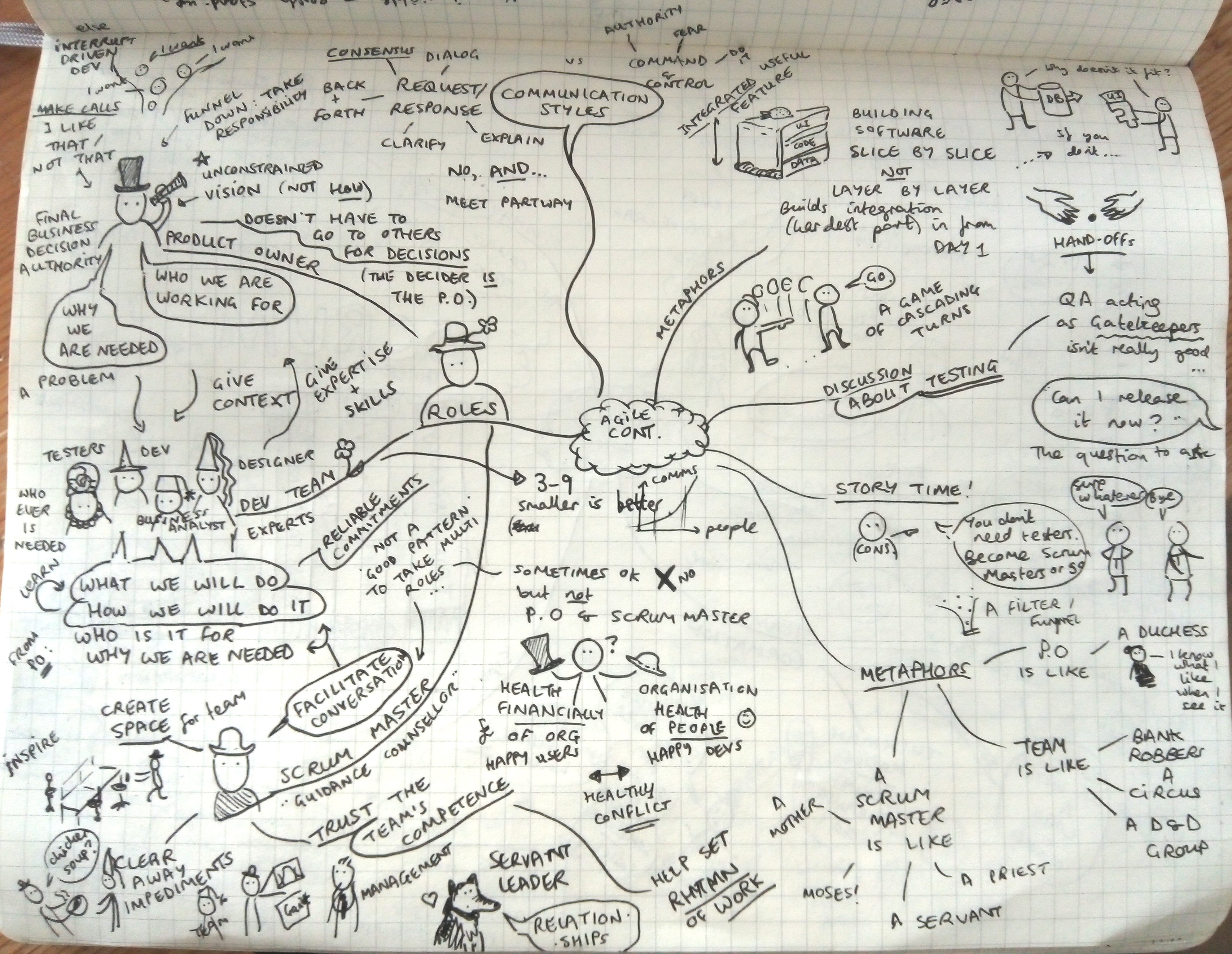

Another exercise I enjoyed was coming up with different metaphors for Scrum. We broke out into groups and thought up some different ideas - I was impressed by the variety and how each of them fitted different parts of what Scrum can look like. Some of my favourites were:

- a garden growing and changing over time

- a cocktail bar developing new drinks

- a stand-up comedian working on their routine

- a graffiti crew making a work of art for their neighbourhood

- Jurassic Park (this was mine!)

A mindmap from my notes about the different Scrum roles

A mindmap from my notes about the different Scrum roles

Following the training, I'm a Certified Scrum Master. There have been some intelligent criticisms of this certification process, including by some of its founders. The fact that there is a certification exam seems to somewhat devalue the training experience itself. I didn't really need to complete the training to do the certification exam - its questions are purely based on the Scrum Guide and a few on the Agile Manifesto. How well can a multiple-choice test about a short document really hope to measure someone's competence in such a fuzzy relationship-centred domain as taking on the role of a Scrum Master? It's always going to fall short, I think. I've acted as a Scrum Master for several years already without the certification, so I was interested to see what it covered and didn't touch on.

I passed the exam. But the things that will really stay with me are the advice of the trainer and the discussions I had during the course, especially with others whose companies are also on the path to adopting more Agile practices. I certainly recommend Tobias as a teacher: his creative exercises and the way he presented the course helped grow my understanding and confidence in the role of Scrum Master. I'd like to attend his Scrum Master Clinic - I think it will really help to have that ongoing mentoring and peer advice.

You're beautiful but I can't work with you.

You're beautiful but I can't work with you. Back to old faithful.

Back to old faithful. By Hans Peter Schaefer - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52728

By Hans Peter Schaefer - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52728

By Simon Letouze - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NGC_006_ngc_front_facia_reduced.jpg

By Simon Letouze - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NGC_006_ngc_front_facia_reduced.jpg The first book I would save from a house fire

The first book I would save from a house fire

They also serve who only stand and watch construction

They also serve who only stand and watch construction I spoke at a virtual conference!

I spoke at a virtual conference! He's very new!

He's very new! Masts of the SS Richard Montgomery. Photo by Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent

Masts of the SS Richard Montgomery. Photo by Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent  Suggested locations of new airport in Thames Estuary. By Ordnance Survey with modifications by Prioryman

Suggested locations of new airport in Thames Estuary. By Ordnance Survey with modifications by Prioryman  Mural by Dean Tweedy made for the Promenade Arts Festival in 2015 - photo Andy Hebden

Mural by Dean Tweedy made for the Promenade Arts Festival in 2015 - photo Andy Hebden This xkcd strip about data pipelines makes me laugh - but it also makes me think about the robustness of my code.

This xkcd strip about data pipelines makes me laugh - but it also makes me think about the robustness of my code.

An example from Long Live The Queen

An example from Long Live The Queen Here's what the board looked like near the start of the two day course.

Here's what the board looked like near the start of the two day course. A mindmap from my notes about the different Scrum roles

A mindmap from my notes about the different Scrum roles